Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and University of Michigan have created the world’s smallest fully programmable, autonomous robots: microscopic swimming machines that can independently sense and respond to their surroundings, operate for months and cost just a penny each.

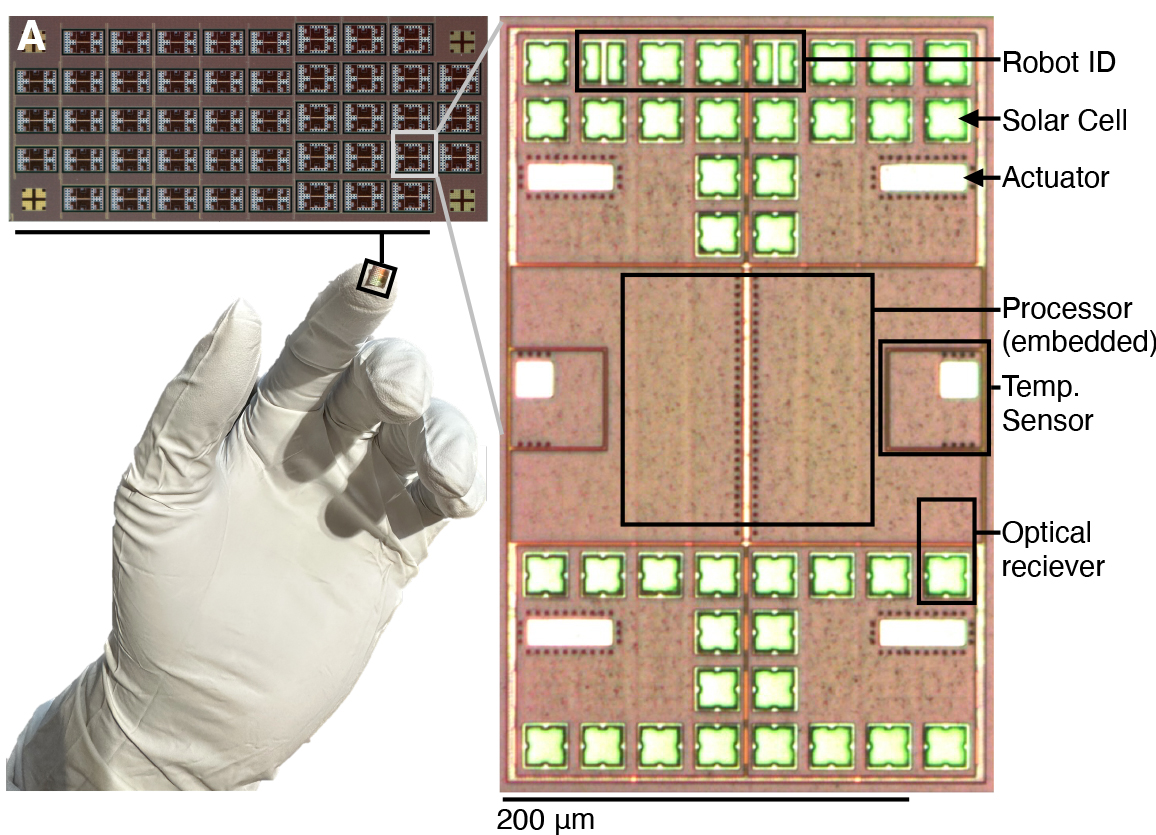

A microrobot, fully integrated with sensors and a computer, small enough to balance on the ridge of a fingerprint. (Credit: Marc Miskin, Penn)

Barely visible to the naked eye, each robot measures about 200 by 300 by 50 micrometers, smaller than a grain of salt. Operating at the scale of many biological microorganisms, the robots could advance medicine by monitoring the health of individual cells and manufacturing by helping construct microscale devices.

Powered by light, the robots carry microscopic computers and can be programmed to move in complex patterns, sense local temperatures and adjust their paths accordingly.

Described in Science Robotics and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the robots operate without tethers, magnetic fields or joystick-like control from the outside, making them the first truly autonomous, programmable robots at this scale.

“We’ve made autonomous robots 10,000 times smaller,” says Marc Miskin, Assistant Professor in Electrical and Systems Engineering at Penn Engineering and the papers’ senior author. “That opens up an entirely new scale for programmable robots.”

[…]

Large aquatic creatures, like fish, move by pushing the water behind them. Thanks to Newton’s Third Law, the water exerts an equal and opposite force on the fish, propelling it forward.

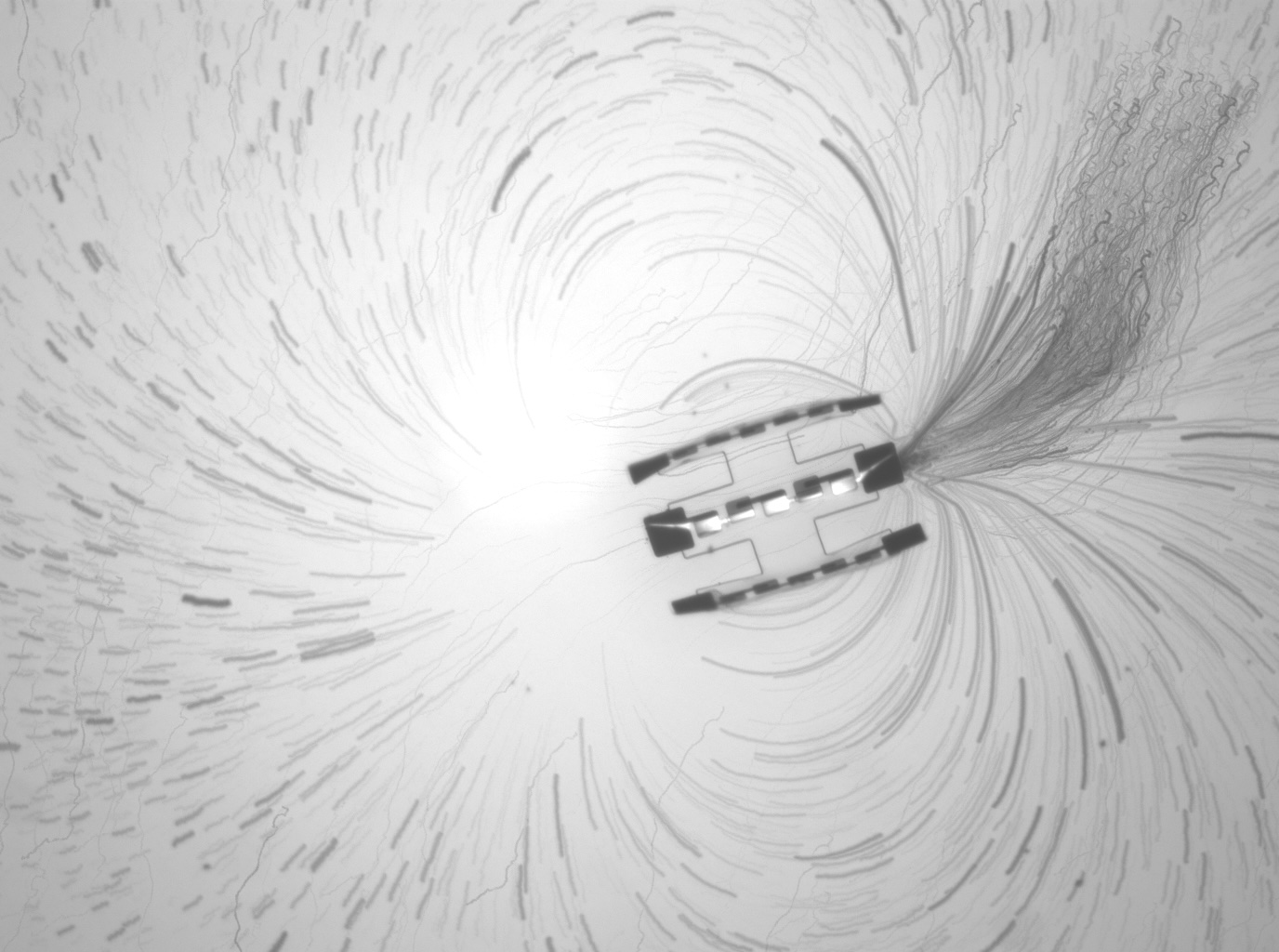

A projected timelapse of tracer particle trajectories near a robot consisting of three motors tied together.. (Credit: Lucas Hanson and William Reinhardt, University of Pennsylvania)

The new robots, by contrast, don’t flex their bodies at all. Rather, they generate an electrical field that nudges ions in the surrounding solution. Those ions, in turn, push on nearby water molecules, animating the water around the robot’s body. “It’s as if the robot is in a moving river,” says Miskin, “but the robot is also causing the river to move.”

The robots can adjust the electrical field that causes the effect, allowing them to move in complex patterns and even travel in coordinated groups, much like a school of fish, at speeds of up to one body length per second.

And because the electrodes that generate the field have no moving parts, the robots are extremely durable. “You can repeatedly transfer these robots from one sample to another using a micropipette without damaging them,” says Miskin. Charged by the glow of an LED, the robots can keep swimming for months on end.

[…]

The robot has a complete onboard computer, which allows it to receive and follow instructions autonomously. (Miskin Lab and Blaauw Lab)

“The key challenge for the electronics,” says Blaauw, “is that the solar panels are tiny and produce only 75 nanowatts of power. That is over 100,000 times less power than what a smart watch consumes.” To run the robot’s computer on such little power, the Michigan team developed special circuits that operate at extremely low voltages and bring down the computer’s power consumption by more than 1000 times.

Still, the solar panels occupy the majority of the space on the robot. Therefore, the second challenge was to cram the processor and memory to store a program in the little space that remained. “We had to totally rethink the computer program instructions,” says Blaauw, “condensing what conventionally would require many instructions for propulsion control into a single, special instruction to shrink the program’s length to fit in the robot’s tiny memory space.”

[…]

The robots have electronic sensors that can detect the temperature to within a third of a degree Celsius. This lets robots move towards areas of increasing temperature, or report the temperature — a proxy for cellular activity — allowing them to monitor the health of individual cells.

“To report out their temperature measurements, we designed a special computer instruction that encodes a value, such as the measured temperature, in the wiggles of a little dance the robot performs,” says Blaauw. “We then look at this dance through a microscope with a camera and decode from the wiggles what the robots are saying to us. It’s very similar to how honey bees communicate with each other.”

The robots are programmed by pulses of light that also power them. Each robot has a unique address that allows the researchers to load different programs on each robot. “This opens up a host of possibilities,” adds Blaauw, “with each robot potentially performing a different role in a larger, joint task.”

Only the Beginning

The final stages of microrobot fabrication deploy hundreds of robots all at once. The tiny machines can then be programmed individually or en masse to carry out experiments. (Credit: Maya Lassiter, University of Pennsylvania)

Future versions of the robots could store more complex programs, move faster, integrate new sensors or operate in more challenging environments. In essence, the current design is a general platform: its propulsion system works seamlessly with electronics, its circuits can be fabricated cheaply at scale and its design allows for adding new capabilities.

[…]

Source: Penn and Michigan Create World’s Smallest Programmable, Autonomous Robots | Penn Engineering

Robin Edgar

Organisational Structures | Technology and Science | Military, IT and Lifestyle consultancy | Social, Broadcast & Cross Media | Flying aircraft