I do understand why so many people, especially creative folks, are worried about AI and how it’s used. The future is quite unknown, and things are changing very rapidly, at a pace that can feel out of control. However, when concern and worry about new technologies and how they may impact things morphs into mob-inspiring fear, dumb things happen. I would much rather that when we look at new things, we take a more realistic approach to them, and look at ways we can keep the good parts of what they provide, while looking for ways to mitigate the downsides.

Hopefully without everyone going crazy in the meantime. Unfortunately, that’s not really the world we live in.

Last year, when everyone was focused on generative AI for images, we had Rob Sheridan on the podcast to talk about why it was important for creative people to figure out how to embrace the technology rather than fear it. The opening story of the recent NY Times profile of me was all about me in a group chat, trying to suggest to some very creative Hollywood folks how to embrace AI rather than simply raging against it. And I’ve already called out how folks rushing to copyright, thinking that will somehow “save” them from AI, are barking up the wrong tree.

But, in the meantime, the fear over AI is leading to some crazy and sometimes unfortunate outcomes. Benji Smith, who created what appears to be an absolutely amazing tool for writers, Shaxpir, also created what looked like an absolutely fascinating tool called Prosecraft, that had scanned and analyzed a whole bunch of books and would let you call up really useful data on books.

He created it years ago, based on an idea he had years earlier, trying to understand the length of various books (which he initially kept in a spreadsheet). As Smith himself describes in a blog post:

I heard a story on NPR about how Kurt Vonnegut invented an idea about the “shapes of stories” by counting happy and sad words. The University of Vermont “Computational Story Lab” published research papers about how this technique could show the major plot points and the “emotional story arc” of the Harry Potter novels (as well as many many other books).

So I tried it myself and found that I could plot a graph of the emotional ups and downs of any story. I added those new “sentiment analysis” tools to the prosecraft website too.

When I ran out of books on my own shelves, I looked to the internet for more text that I could analyze, and I used web crawlers to find more books. I wanted to be mindful of the diversity of different stories, so I tried to find books by authors of every race and gender, from every different cultural and political background, writing in every different genre and exploring all different kinds of themes. Fiction and nonfiction and philosophy and science and religion and culture and politics.

Somewhere out there on the internet, I thought to myself, there was a new author writing a horror or romance or fantasy novel, struggling for guidance about how long to write their stories, how to write more vivid prose, and how much “passive voice” was too much or too little.

I wanted to give those budding storytellers a suite of “lexicographic” tools that they could use, to compare their own writing with the writing of authors they admire. I’ve been working in the field of computational linguistics and machine learning for 20+ years, and I was always frustrated that the fancy tools were only accessible to big businesses and government spy agencies. I wanted to bring that magic to everyone.

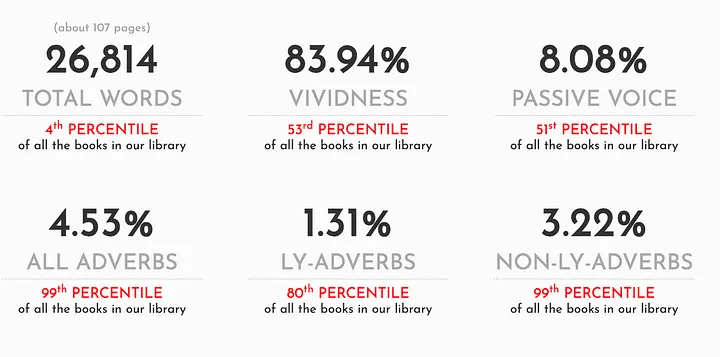

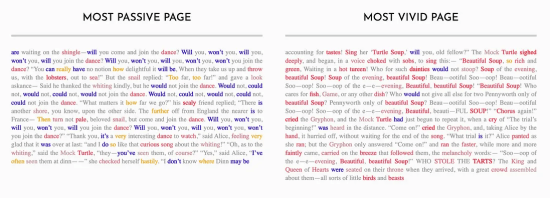

Frankly, all of that sounds amazing. And amazingly useful. Even more amazing is that he built it, and it worked. It would produce useful analysis of books, such as this example from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland:

And, it could also do further analysis like the following:

This is all quite interesting. It’s also the kind of thing that data scientists do on all kinds of work for useful purposes.

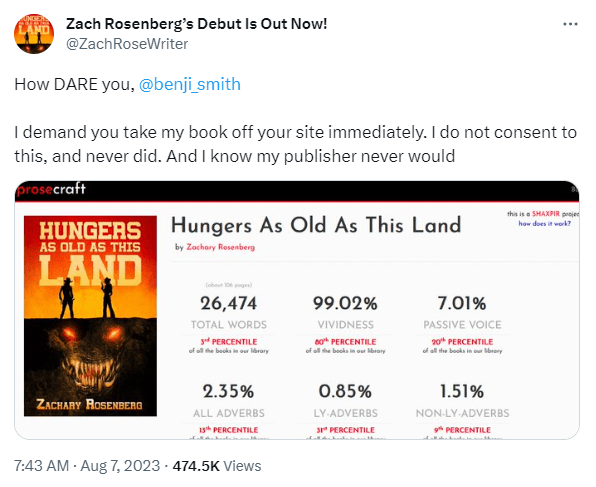

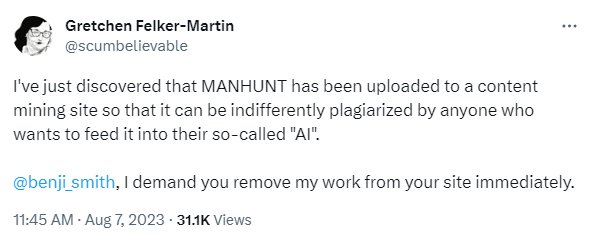

Smith built Prosecraft into Shaxpir, again, making it a more useful tool. But, on Monday, some authors on the internet found out about it and lost their shit, leading Smith to shut the whole project down.

There seems to be a lot of misunderstanding about all of this. Smith notes that he had researched the copyright issues and was sure he wasn’t violating anything, and he’s right. We’ve gone over this many times before. Scanning books is pretty clearly fair use. What you do with that later could violate copyright law, but I don’t see anything that Prosecraft did that comes anywhere even remotely close to violating copyright law.

But… some authors got pretty upset about all of it.

I’m still perplexed at what the complaint is here? You don’t need to “consent” for someone to analyze your book. You don’t need to “consent” to someone putting up statistics about their analysis of your book.

But, Zach’s tweet went viral with a bunch of folks ready to blow up anything that smacks of tech bro AI, and lots of authors started yelling at Smith.

The Gizmodo article has a ridiculously wrong “fair use” analysis, saying “Fair Use does not, by any stretch of the imagination, allow you to use an author’s entire copyrighted work without permission as a part of a data training program that feeds into your own ‘AI algorithm.’” Except… it almost certainly does? Again, we’ve gone through this with the Google Book scanning case, and the courts said that you can absolutely do that because it’s transformative.

It seems that what really tripped up people here was the “AI” part of it, and the fear that this was just another a VC funded “tech bro” exercise of building something to get rich by using the works of creatives. Except… none of that is accurate. As Smith explained in his blog post:

For what it’s worth, the prosecraft website has never generated any income. The Shaxpir desktop app is a labor of love, and during most of its lifetime, I’ve worked other jobs to pay the bills while trying to get the company off the ground and solve the technical challenges of scaling a startup with limited resources. We’ve never taken any VC money, and the whole company is a two-person operation just working our hardest to serve our small community of authors.

He also recognizes that the concerns about it being some “AI” thing are probably what upset people, but plenty of authors have found the tool super useful, and even added their own books:

I launched the prosecraft website in the summer of 2017, and I started showing it off to authors at writers conferences. The response was universally positive, and I incorporated the prosecraft analytic tools into the Shaxpir desktop application so that authors could privately run these analytics on their own works-in-progress (without ever sharing those analyses publicly, or even privately with us in our cloud).

I’ve spent thousands of hours working on this project, cleaning up and annotating text, organizing and tweaking things. A small handful of authors have even reached out to me, asking to have their books added to the website. I was grateful for their enthusiasm.

But in the meantime, “AI” became a thing.

And the arrival of AI on the scene has been tainted by early use-cases that allow anyone to create zero-effort impersonations of artists, cutting those creators out of their own creative process.

That’s not something I ever wanted to participate in.

Smith took the project down entirely because of that. He doesn’t want to get lumped in with other projects, and even though his project is almost certainly legal, he recognized that this was becoming an issue:

Today the community of authors has spoken out, and I’m listening. I care about you, and I hear your objections.

Your feelings are legitimate, and I hope you’ll accept my sincerest apologies. I care about stories. I care about publishing. I care about authors. I never meant to hurt anyone. I only hoped to make something that would be fun and useful and beautiful, for people like me out there struggling to tell their own stories.

I find all of this really unfortunate. Smith built something really cool, really amazing, that does not, in any way, infringe on anyone’s rights. I get the kneejerk reaction from some authors, who feared that this was some obnoxious project, but couldn’t they have taken 10 minutes to look at the details of what it was they were killing?

I know we live in an outrage era, where the immediate reaction is to turn the outrage meter up to 11. I’m certainly guilty of that at times myself. But this whole incident is just sad. It was an overreaction from the start, destroying what had been a clear labor of love and a useful project, through misleading and misguided attacks from authors.