[…]A research team at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory has created a novel advanced microscopy tool to “write” with atoms, placing those atoms exactly where they are needed to give a material new properties.

“By working at the atomic scale, we also work at the scale where quantum properties naturally emerge and persist,” said Stephen Jesse, a materials scientist who leads this research and heads the Nanomaterials Characterizations section at ORNL’s Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences, or CNMS.

[…]

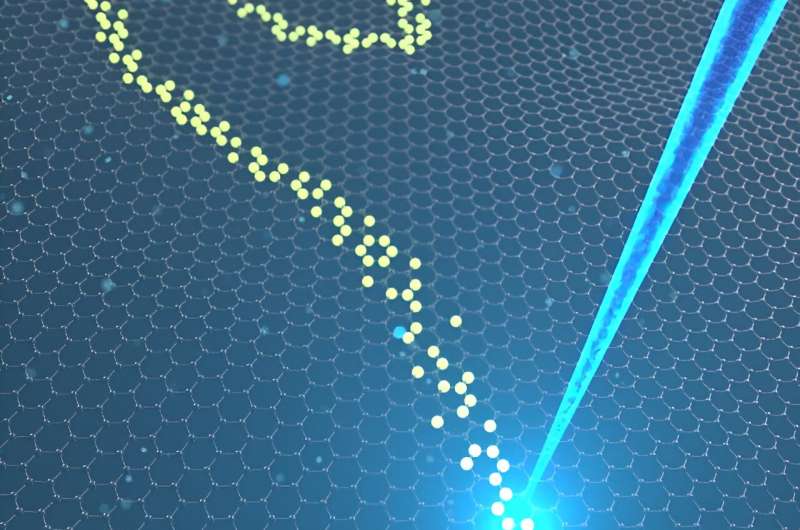

o accomplish improved control over atoms, the research team created a tool they call a synthescope for combining synthesis with advanced microscopy. The researchers use a scanning transmission electron microscope, or STEM, transformed into an atomic-scale material manipulation platform.

The synthescope will advance the state of the art in fabrication down to the level of the individual building blocks of materials. This new approach allows researchers to place different atoms into a material at specific locations; the new atoms and their locations can be selected to give the material new properties.

[…]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I5FSc-lqI6s

We realized that if we have a microscope that can resolve atoms, we may be able to use the same microscope to move atoms or alter materials with atomic precision. We also want to be able to add atoms to the structures we create, so we need a supply of atoms. The idea morphed into an atomic-scale synthesis platform—the synthescope.”

That is important because the ability to tailor materials atom-by-atom can be applied to many future technological applications in quantum information science, and more broadly in microelectronics and catalysis, and for gaining a deeper understanding of materials synthesis processes. This work could facilitate atomic-scale manufacturing, which is notoriously challenging.

“Simply by the fact that we can now start putting atoms where we want, we can think about creating arrays of atoms that are precisely positioned close enough together that they can entangle, and therefore share their quantum properties, which is key to making quantum devices more powerful than conventional ones,” Dyck said.

Such devices might include quantum computers—a proposed next generation of computers that may vastly outpace today’s fastest supercomputers; quantum sensors; and quantum communication devices that require a source of a single photon to create a secure quantum communications system.

“We are not just moving atoms around,” Jesse said. “We show that we can add a variety of atoms to a material that were not previously there and put them where we want them. Currently there is no technology that allows you to place different elements exactly where you want to place them and have the right bonding and structure. With this technology, we could build structures from the atom up, designed for their electronic, optical, chemical or structural properties.”

The scientists, who are part of the CNMS, a nanoscience research center and DOE Office of Science user facility, detailed their research and their vision in a series of four papers in scientific journals over the course of a year, starting with proof of principle that the synthescope could be realized. They have applied for a patent on the technology.

“With these papers, we are redirecting what atomic-scale fabrication will look like using electron beams,” Dyck said. “Together these manuscripts outline what we believe will be the direction atomic fabrication technology will take in the near future and the change in conceptualization that is needed to advance the field.”

By using an electron beam, or e-beam, to remove and deposit the atoms, the ORNL scientists could accomplish a direct writing procedure at the atomic level.

“The process is remarkably intuitive,” said ORNL’s Andrew Lupini, STEM group leader and a member of the research team. “STEMs work by transmitting a high-energy e-beam through a material. The e-beam is focused to a point smaller than the distance between atoms and scans across the material to create an image with atomic resolution. However, STEMs are notorious for damaging the very materials they are imaging.”

The scientists realized they could exploit this destructive “bug” and instead use it as a constructive feature and create holes on purpose. Then, they can put whatever atom they want in that hole, exactly where they made the defect. By purposely damaging the material, they create a new material with different and useful properties.

[…]

To demonstrate the method, the researchers moved an e-beam back and forth over a graphene lattice, creating minuscule holes. They inserted tin atoms into those holes and achieved a continuous, atom-by-atom, direct writing process, thereby populating the exact same places where the carbon atom had been with tin atoms.

[…]

Source: ‘Writing’ with atoms could transform materials fabrication for quantum devices