A few weeks ago, the UK’s regional and national daily news titles ran similar front covers, exhorting the government there to “Make it Fair”. The campaign Web site explained:

Tech companies use creative content, such as news articles, books, music, film, photography, visual art, and all kinds of creative work, to train their generative AI models.

Publishers and creators say that doing this without proper controls, transparency or fair payment is unfair and threatens their livelihoods.

Under new UK proposals, creators will be able to opt out of their works being used for training purposes, but the current campaign wants more than that:

Creators argue this [opt-out] puts the burden on them to police their work and that tech companies should pay for using their content.

The campaign Web site then uses a familiar trope:

Tech giants should not profit from stolen content, or use it for free.

But the material is not stolen, it is simply analysed as part of the AI training. Analysing texts or images is about knowledge acquisition, not copyright infringement. Once again, the copyright industries are trying to place a (further) tax on knowledge. Moreover, levying that tax is completely impractical. Since there is no way to determine which works were used during training to produce any given output, the payments would have to be according to their contribution to the training material that went into creating the generative AI system itself. A Walled Culture post back in October 2023 noted that the amounts would be extremely small, because of the sheer quantity of training data that is used. Any monies collected from AI companies would therefore have to be handed over in aggregate, either to yet another inefficient collection society, or to the corporate intermediaries. For this reason, there is no chance that creators would benefit significantly from any AI tax.

We’ve been here before. Five years ago, I wrote a post about the EU Copyright Directive’s plans for an ancillary copyright, also known as the snippet or link tax. One of the key arguments by the newspaper publishers was that this new tax was needed so that journalists were compensated when their writing appeared in search results and elsewhere. As I showed back then, the amounts involved would be negligible. In fact, few EU countries have even bothered to implement the provision on allocating a share to journalists, underlining how pointless it all was. At the time, the European Commission insisted on behalf of its publishing friends that ancillary copyright was absolutely necessary because:

The organisational and financial contribution of publishers in producing press publications needs to be recognised and further encouraged to ensure the sustainability of the publishing industry.

Now, on the new Make it Fair Web site we find a similar claim about sustainability:

We’re calling on the government to ensure creatives are rewarded properly so as to ensure a sustainable future for AI and the creative industries.

As with the snippet tax, an AI tax is not going to do that, since the sums involved as so small. A post on the News Media Association reveals what is the real issue here:

The UK’s creative industries have today launched a bold campaign to highlight how their content is at risk of being given away for free to AI firms as the government proposes weakening copyright law.

Walled Culture has noted many times it is a matter of dogma for the industries involved that copyright must only ever get stronger, as if they were a copyright ratchet. The fear is evidently that once it has been “weakened” in some way, a precedent would be set, and other changes might be made to give more rights to ordinary people (perish the thought) rather than to companies. It’s worth pointing out that the copyright world is deploying its usual sleight of hand here, writing:

The government must stand with the creative industries that make Britain great and enforce our copyright laws to allow creatives to assert their rights in the age of AI.

A fair deal for artists and writers isn’t just about making things right, it is essential for the future of creativity and AI.

Who could be against this call for the UK government to defend the poor artists and writers? No one, surely? But the way to do that, according to Make it Fair, is to “stand with the creative industries”. In other words, give the big copyright companies more power to act as gatekeepers, on the assumption that their interests are perfectly aligned with those of the struggling creators.

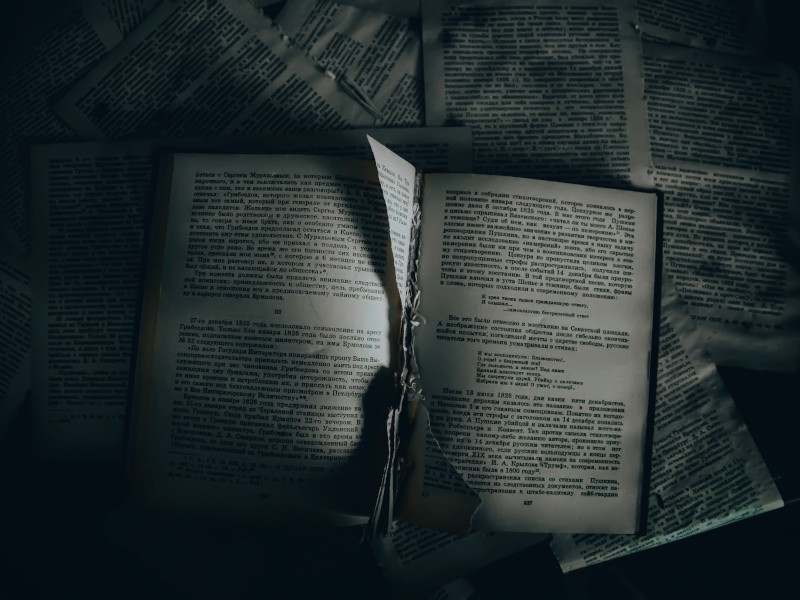

They are not. As Walled Culture the book explores in some detail (free digital versions available), the vast majority of those “artists and writers” invoked by the “Make it Fair” campaign are unable to make a decent living from their work under copyright. Meanwhile, huge global corporations enjoy fat profits as a result of that same creativity, but give very little back to the people who did all the work.

There are serious problems with the new AI offerings, and big tech companies definitely need to be reined in for many things, but not for their basic analysis of text and images. If publishers really want to “Make it Fair”, they should start by rewarding their own authors fairly, with more than the current pittance. And if they won’t do that, as seems likely given their history of exploitation, creators should explore some of the ways they can make a decent living without them. Notably, many of these have no need for a copyright system that is the epitome of unfairness, which is precisely why publishers are so desperate to defend it in this latest coordinated campaign.