Smart cities are designed to make life easier for their residents: better traffic management by clearing routes, making sure the public transport is running on time and having cameras keeping a watchful eye from above.

But what happens when that data leaks? One such database was open for weeks for anyone to look inside.

Security researcher John Wethington found a smart city database accessible from a web browser without a password. He passed details of the database to TechCrunch in an effort to get the data secured.

[…]

he system monitors the residents around at least two small housing communities in eastern Beijing, the largest of which is Liangmaqiao, known as the city’s embassy district. The system is made up of several data collection points, including cameras designed to collect facial recognition data.

The exposed data contains enough information to pinpoint where people went, when and for how long, allowing anyone with access to the data — including police — to build up a picture of a person’s day-to-day life.

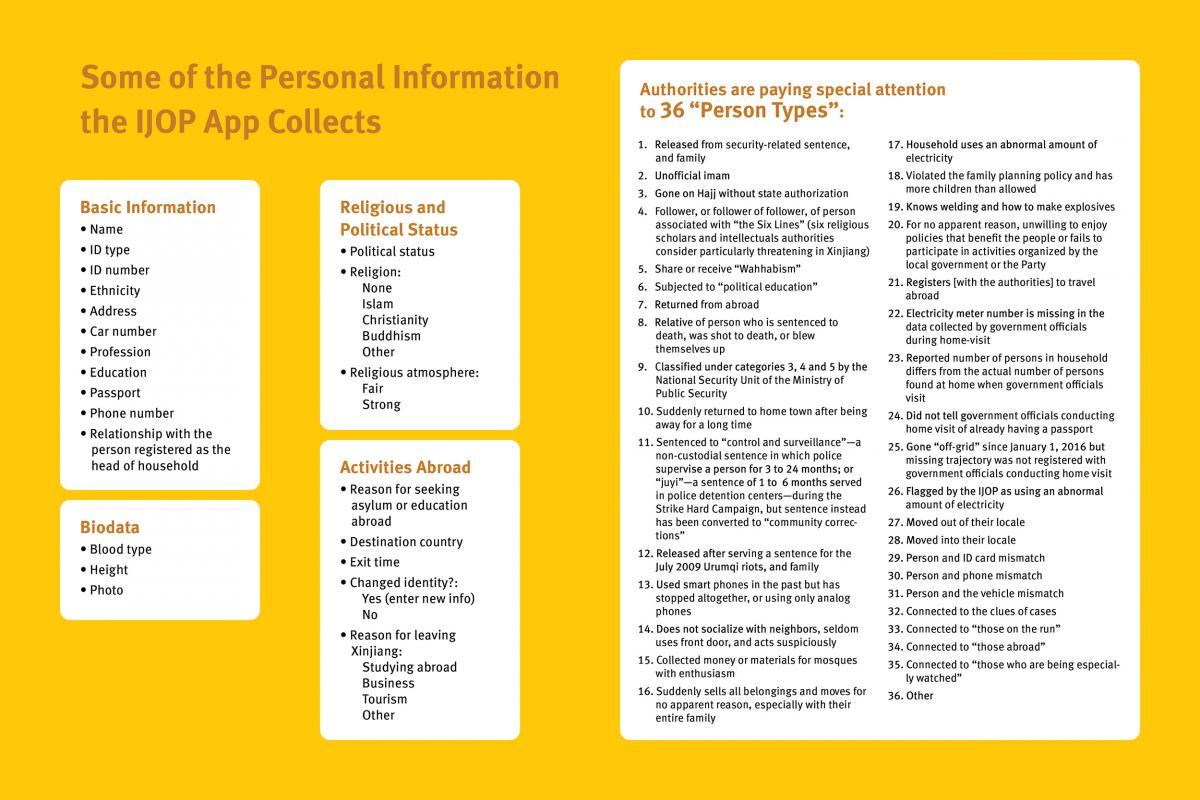

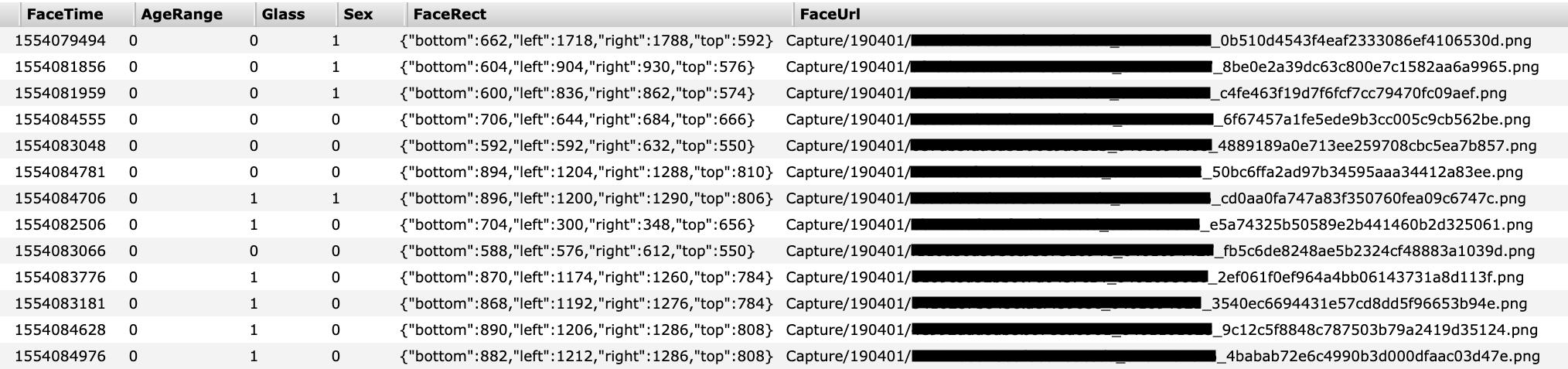

A portion of the database containing facial recognition scans (Image: supplied)

The database processed various facial details, such as if a person’s eyes or mouth are open, if they’re wearing sunglasses, or a mask — common during periods of heavy smog — and if a person is smiling or even has a beard.

The database also contained a subject’s approximate age as well as an “attractive” score, according to the database fields.

But the capabilities of the system have a darker side, particularly given the complicated politics of China.

The system also uses its facial recognition systems to detect ethnicities and labels them — such as “汉族” for Han Chinese, the main ethnic group of China — and also “维族” — or Uyghur Muslims, an ethnic minority under persecution by Beijing.

Where ethnicities can help police identify suspects in an area even if they don’t have a name to match, the data can be used for abuse.

The Chinese government has detained more than a million Uyghurs in internment camps in the past year, according to a United Nations human rights committee. It’s part of a massive crackdown by Beijing on the ethnic minority group. Just this week, details emerged of an app used by police to track Uyghur Muslims.

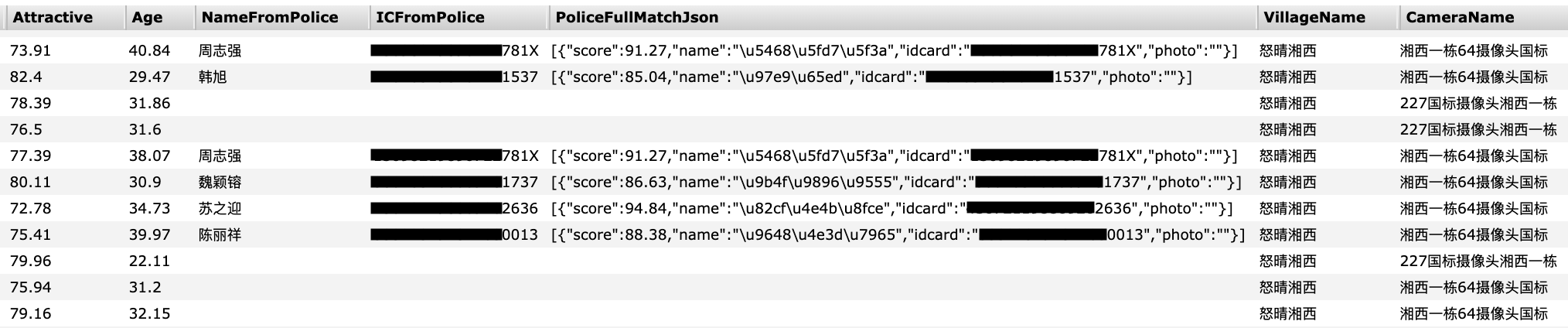

We also found that the customer’s system also pulls in data from the police and uses that information to detect people of interest or criminal suspects, suggesting it may be a government customer.

Facial recognition scans would match against police records in real time (Image: supplied)

Each time a person is detected, the database would trigger a “warning” noting the date, time, location and a corresponding note. Several records seen by TechCrunch include suspects’ names and their national identification card number.