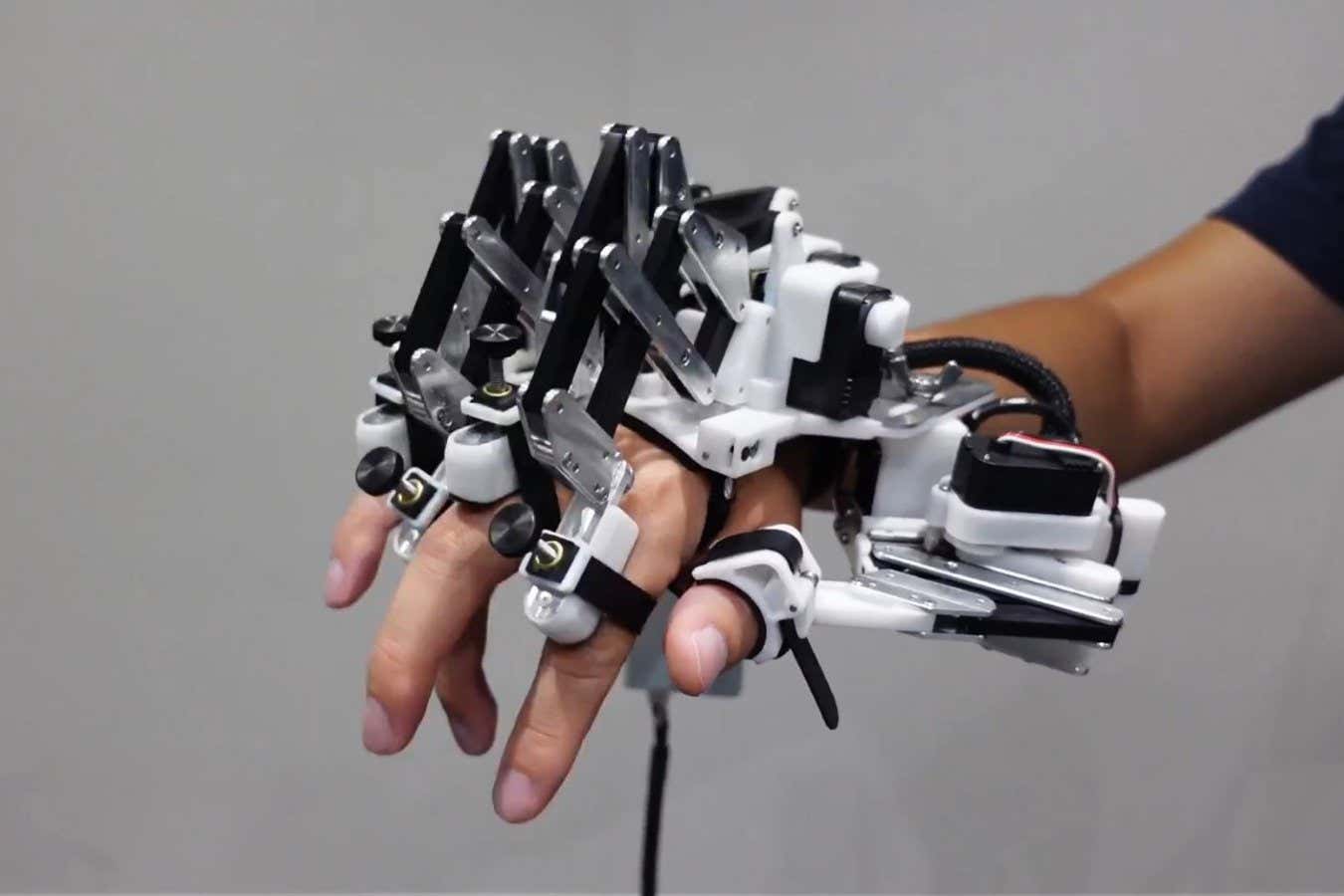

You can probably complete an amazing number of tasks with your hands without looking at them. But if you put on gloves that muffle your sense of touch, many of those simple tasks become frustrating. Take away proprioception — your ability to sense your body’s relative position and movement — and you might even end up breaking an object or injuring yourself.

[…]

Greenspon and his research collaborators recently published papers in Nature Biomedical Engineering and Science documenting major progress on a technology designed to address precisely this problem: direct, carefully timed electrical stimulation of the brain that can recreate tactile feedback to give nuanced “feeling” to prosthetic hands.

[…]

The researchers’ approach to prosthetic sensation involves placing tiny electrode arrays in the parts of the brain responsible for moving and feeling the hand. On one side, a participant can move a robotic arm by simply thinking about movement, and on the other side, sensors on that robotic limb can trigger pulses of electrical activity called intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) in the part of the brain dedicated to touch.

For about a decade, Greenspon explained, this stimulation of the touch center could only provide a simple sense of contact in different places on the hand.

“We could evoke the feeling that you were touching something, but it was mostly just an on/off signal, and often it was pretty weak and difficult to tell where on the hand contact occurred,” he said.

[…]

By delivering short pulses to individual electrodes in participants’ touch centers and having them report where and how strongly they felt each sensation, the researchers created detailed “maps” of brain areas that corresponded to specific parts of the hand. The testing revealed that when two closely spaced electrodes are stimulated together, participants feel a stronger, clearer touch, which can improve their ability to locate and gauge pressure on the correct part of the hand.

The researchers also conducted exhaustive tests to confirm that the same electrode consistently creates a sensation corresponding to a specific location.

“If I stimulate an electrode on day one and a participant feels it on their thumb, we can test that same electrode on day 100, day 1,000, even many years later, and they still feel it in roughly the same spot,” said Greenspon, who was the lead author on this paper.

[…]

The complementary Science paper went a step further to make artificial touch even more immersive and intuitive. The project was led by first author Giacomo Valle, PhD, a former postdoctoral fellow at UChicago who is now continuing his bionics research at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden.

“Two electrodes next to each other in the brain don’t create sensations that ’tile’ the hand in neat little patches with one-to-one correspondence; instead, the sensory locations overlap,” explained Greenspon, who shared senior authorship of this paper with Bensmaia.

The researchers decided to test whether they could use this overlapping nature to create sensations that could let users feel the boundaries of an object or the motion of something sliding along their skin. After identifying pairs or clusters of electrodes whose “touch zones” overlapped, the scientists activated them in carefully orchestrated patterns to generate sensations that progressed across the sensory map.

Participants described feeling a gentle gliding touch passing smoothly over their fingers, despite the stimulus being delivered in small, discrete steps. The scientists attribute this result to the brain’s remarkable ability to stitch together sensory inputs and interpret them as coherent, moving experiences by “filling in” gaps in perception.

The approach of sequentially activating electrodes also significantly improved participants’ ability to distinguish complex tactile shapes and respond to changes in the objects they touched. They could sometimes identify letters of the alphabet electrically “traced” on their fingertips, and they could use a bionic arm to steady a steering wheel when it began to slip through the hand.

These advancements help move bionic feedback closer to the precise, complex, adaptive abilities of natural touch, paving the way for prosthetics that enable confident handling of everyday objects and responses to shifting stimuli.

[…]

“We hope to integrate the results of these two studies into our robotics systems, where we have already shown that even simple stimulation strategies can improve people’s abilities to control robotic arms with their brains,” said co-author Robert Gaunt, PhD, associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation and lead of the stimulation work at the University of Pittsburgh.

Greenspon emphasized that the motivation behind this work is to enhance independence and quality of life for people living with limb loss or paralysis.

[…]