23andMe is a terrific concept. In essence, the company takes a sample of your DNA and tells you about your genetic makeup. For some of us, this is the only way to learn about our heritage. Spotty records, diaspora, mistaken family lore and slavery can make tracing one’s roots incredibly difficult by traditional methods.

What 23andMe does is wonderful because your DNA is fixed. Your genes tell a story that supersedes any rumors that you come from a particular country or are descended from so-and-so.

[…]

ou can replace your Social Security number, albeit with some hassle, if it is ever compromised. You can cancel your credit card with the click of a button if it is stolen. But your DNA cannot be returned for a new set — you just have what you are given. If bad actors steal or sell your genetic information, there is nothing you can do about it.

This is why 23andMe’s Oct. 6 data leak, although it reads like science fiction, is not an omen of some dark future. It is, rather, an emblem of our dangerous present.

23andMe has a very simple interface with some interesting features. “DNA Relatives” matches you with other members to whom you are related. This could be an effective, thoroughly modern way to connect with long-lost family, or to learn more about your origins.

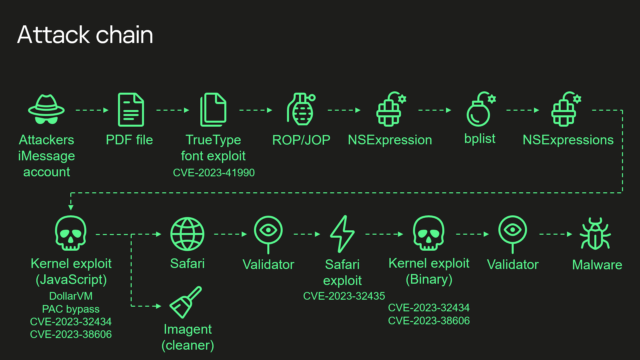

But the Oct. 6 leak perverted this feature into something alarming. By gaining access to individual accounts through weak and recycled passwords, hackers were able to create an extensive list of people with Ashkenazi heritage. This list was then posted on forums with the names, sex and likely heritage of each member under the title “Ashkenazi DNA Data of Celebrities.”

First and foremost, collecting lists of people based on their ethnic backgrounds is a personal violation with tremendously insidious undertones. If you saw yourself and your extended family on such a list, you would not take it lightly.

[…]

I find it troubling because, in 2018, Time reported that 23andMe had sold a $300 million stake in its business to GlaxoSmithKline, allowing the pharmaceutical giant to use users’ genetic data to develop new drugs. So because you wanted to know if your grandmother was telling the truth about your roots, you spat into a cup and paid 23andMe to give your DNA to a drug company to do with it as they please.

Although 23andMe is in the crosshairs of this particular leak, there are many companies in murky waters. Last year, Consumer Reports found that 23andMe and its competitors had decent privacy policies where DNA was involved, but that these businesses “over-collect personal information about you and overshare some of your data with third parties…CR’s privacy experts say it’s unclear why collecting and then sharing much of this data is necessary to provide you the services they offer.”

[…]

. As it stands, your DNA can be weaponized against you by law enforcement, insurance companies, and big pharma. But this will not be limited to you. Your DNA belongs to your whole family.

Pretend that you are going up against one other candidate for a senior role at a giant corporation. If one of these genealogy companies determines that you are at an outsized risk for a debilitating disease like Parkinson’s and your rival is not, do you think that this corporation won’t take that into account?

[…]

Insurance companies are not in the business of losing money either. If they gain access to such a thing that on your record, you can trust that they will use it to blackball you or jack up your rates.

In short, the world risks becoming like that of the film Gattaca, where the genetic elite enjoy access while those deemed genetically inferior are marginalized.

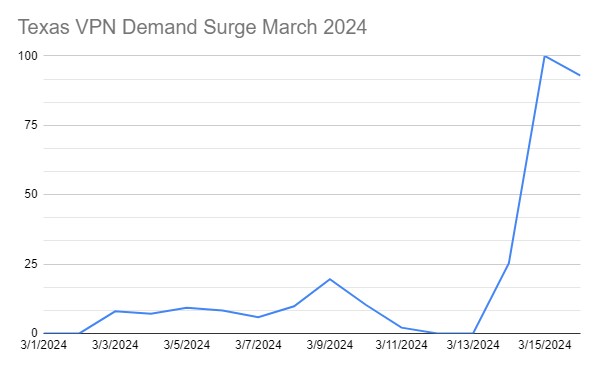

The train has left the station for a lot of these issues. That list of people from the 23andMe leak cannot put the genie back in the bottle. If your DNA is on a server for one of these companies, there is a chance that it has already been used as a reference or to help pharmaceutical companies.

[…]

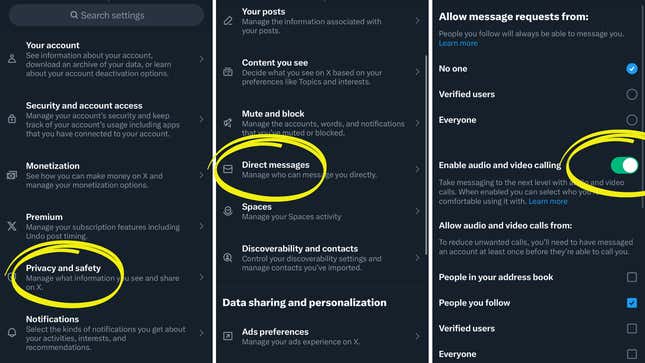

There are things they can do now to avoid further damage. The next time a company asks for something like your phone number or SSN, press them as to why they need it. Make it inconvenient for them to mine you for your Personal Identifiable Information (PII). Your PII has concrete value to these places, and they count on people to be passive, to hand it over without any fuss.

[…]

The time to start worrying about this problem was 20 years ago, but we can still affect positive change today. This 23andMe leak is only the beginning; we must do everything possible to protect our identities and DNA while they still belong to us.

Source: Bad genes: 23andMe leak highlights a possible future of genetic discrimination | The Hill

Scientific American was warning about this since at least 2013. What have we done? Nothing.:

If there’s a gene for hubris, the 23andMe crew has certainly got it. Last Friday the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ordered the genetic-testing company immediately to stop selling its flagship product, its $99 “Personal Genome Service” kit. In response, the company cooed that its “relationship with the FDA is extremely important to us” and continued hawking its wares as if nothing had happened. Although the agency is right to sound a warning about 23andMe, it’s doing so for the wrong reasons.

Since late 2007, 23andMe has been known for offering cut-rate genetic testing. Spit in a vial, send it in, and the company will look at thousands of regions in your DNA that are known to vary from human to human—and which are responsible for some of our traits

[…]

Everything seemed rosy until, in what a veteran Forbes reporter calls “the single dumbest regulatory strategy [he had] seen in 13 years of covering the Food and Drug Administration,” 23andMe changed its strategy. It apparently blew through its FDA deadlines, effectively annulling the clearance process, and abruptly cut off contact with the agency in May. Adding insult to injury the company started an aggressive advertising campaign (“Know more about your health!”)

[…]

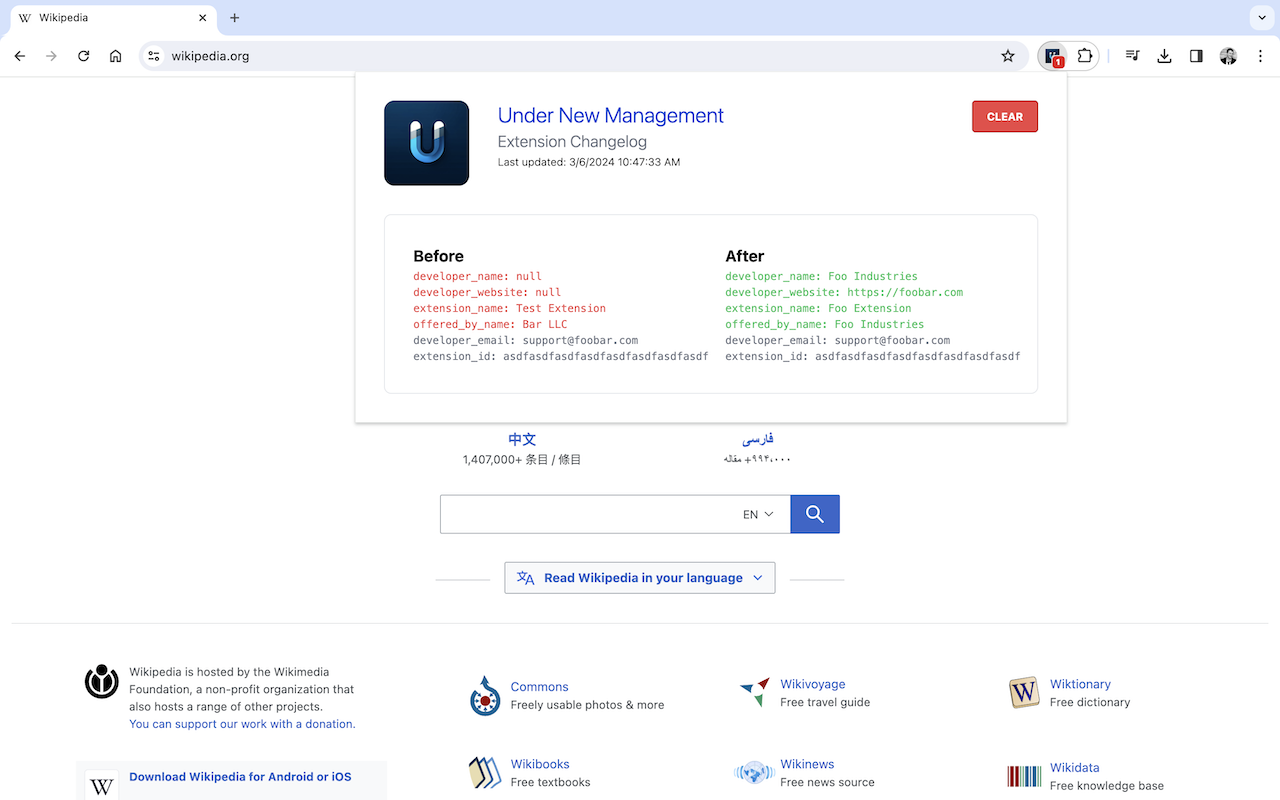

But as the FDA frets about the accuracy of 23andMe’s tests, it is missing their true function, and consequently the agency has no clue about the real dangers they pose. The Personal Genome Service isn’t primarily intended to be a medical device. It is a mechanism meant to be a front end for a massive information-gathering operation against an unwitting public.

Sound paranoid? Consider the case of Google. (One of the founders of 23andMe, Anne Wojcicki, is presently married to Sergei Brin, the founder of Google.) When it first launched, Google billed itself as a faithful servant of the consumer, a company devoted only to building the best tool to help us satisfy our cravings for information on the web. And Google’s search engine did just that. But as we now know, the fundamental purpose of the company wasn’t to help us search, but to hoard information. Every search query entered into its computers is stored indefinitely. Joined with information gleaned from cookies that Google plants in our browsers, along with personally identifiable data that dribbles from our computer hardware and from our networks, and with the amazing volumes of information that we always seem willing to share with perfect strangers—even corporate ones—that data store has become Google’s real asset

[…]

23andMe reserves the right to use your personal information—including your genome—to inform you about events and to try to sell you products and services. There is a much more lucrative market waiting in the wings, too. One could easily imagine how insurance companies and pharmaceutical firms might be interested in getting their hands on your genetic information, the better to sell you products (or deny them to you).

[…]

ven though 23andMe currently asks permission to use your genetic information for scientific research, the company has explicitly stated that its database-sifting scientific work “does not constitute research on human subjects,” meaning that it is not subject to the rules and regulations that are supposed to protect experimental subjects’ privacy and welfare.

Those of us who have not volunteered to be a part of the grand experiment have even less protection. Even if 23andMe keeps your genome confidential against hackers, corporate takeovers, and the temptations of filthy lucre forever and ever, there is plenty of evidence that there is no such thing as an “anonymous” genome anymore. It is possible to use the internet to identify the owner of a snippet of genetic information and it is getting easier day by day.

This becomes a particularly acute problem once you realize that every one of your relatives who spits in a 23andMe vial is giving the company a not-inconsiderable bit of your own genetic information to the company along with their own. If you have several close relatives who are already in 23andMe’s database, the company already essentially has all that it needs to know about you.

[…]

Source: 23andMe Is Terrifying, but Not for the Reasons the FDA Thinks