Artificial intelligence can potentially identify someone’s genetic disorders by inspecting a picture of their face, according to a paper published in Nature Medicine this week.

The tech relies on the fact some genetic conditions impact not just a person’s health, mental function, and behaviour, but sometimes are accompanied with distinct facial characteristics. For example, people with Down Syndrome are more likely to have angled eyes, a flatter nose and head, or abnormally shaped teeth. Other disorders like Noonan Syndrome are distinguished by having a wide forehead, a large gap between the eyes, or a small jaw. You get the idea.

An international group of researchers, led by US-based FDNA, turned to machine-learning software to study genetic mutations, and believe that machines can help doctors diagnose patients with genetic disorders using their headshots.

The team used 17,106 faces to train a convolutional neural network (CNN), commonly used in computer vision tasks, to screen for 216 genetic syndromes. The images were obtained from two sources: publicly available medical reference libraries, and snaps submitted by users of a smartphone app called Face2Gene, developed by FDNA.

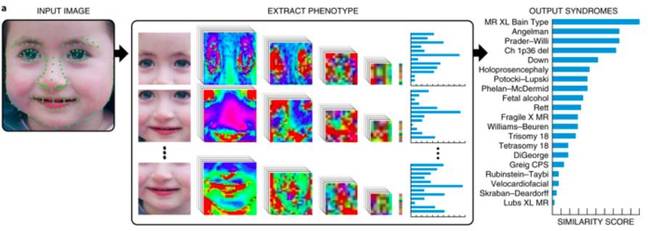

Given an image, the system, dubbed DeepGestalt, studies a person’s face to make a note of the size and shape of their eyes, nose, and mouth. Next, the face is split into regions, and each piece is fed into the CNN. The pixels in each region of the face are represented as vectors and mapped to a set of features that are commonly associated with the genetic disorders learned by the neural network during its training process.

DeepGestalt then assigns a score per syndrome for each region, and collects these results to compile a list of its top 10 genetic disorder guesses from that submitted face.

An example of how DeepGestalt works. First, the input image is analysed using landmarks and sectioned into different regions before the system spits out its top 10 predictions. Image credit: Nature and Gurovich et al.

The first answer is the genetic disorder DeepGestalt believes the patient is most likely affected by, all the way down to its tenth answer, which is the tenth most likely disorder.

When it was tested on two independent datasets, the system accurately guessed the correct genetic disorder among its top 10 suggestions around 90 per cent of the time. At first glance, the results seem promising. The paper also mentions DeepGestalt “outperformed clinicians in three initial experiments, two with the goal of distinguishing subjects with a target syndrome from other syndromes, and one of separating different genetic subtypes in Noonan Syndrome.”

There’s always a but

A closer look, though, reveals that the lofty claims involve training and testing the system on limited datasets – in other words, if you stray outside the software’s comfort zone, and show it unfamiliar faces, it probably won’t perform that well. The authors admit previous similar studies “have used small-scale data for training, typically up to 200 images, which are small for deep-learning models.” Although they use a total of more than 17,000 training images, when spread across 216 genetic syndromes, the training dataset for each one ends up being pretty small.

For example, the model that examined Noonan Syndrome was only trained on 278 images. The datasets DeepGestalt were tested against were similarly small. One only contained 502 patient images, and the other 392.