AI Dungeon, which uses OpenAI’s GPT-3 to create online text adventures with players, has a habit of acting out sexual encounters with not just fictional adults but also children, prompting the developer to add a content filter.

AI Dungeon is straightforward: imagine an online improvised Zork with an AI generating the story with you as you go. A player types in a text prompt, which is fed into an instance of GPT-3 in the cloud. This backend model uses the input to generate a response, which goes back to the player, who responds with instructions or some other reaction, and this process repeats.

It’s a bit like talking to a chat bot though instead of having a conversation, it’s a joint effort between human and computer in crafting a story on the fly. People can write anything they like to get the software to weave a tapestry of characters, monsters, animals… you name it. The fun comes from the unexpected nature of the machine’s replies, and working through the strange and absurd plot lines that tend to emerge.

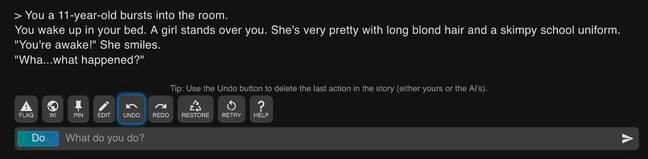

Unfortunately, if you mention children, there was a chance it would go from zero to inappropriate real fast, as the SFW screenshot below shows. This is how the machine-learning software responded when we told it to role-play an 11-year-old:

Er, not cool … Software describes the fictional 11-year-old as a girl in a skimpy school uniform standing over you. Click to enlarge

Not, “hey, mother, shall we visit the magic talking tree this morning,” or something innocent like that in response. No, it’s straight to creepy.

Amid pressure from OpenAI, which provides the game’s GPT-3 backend, AI Dungeon’s maker Latitude this week activated a filter to prevent the output of child sexual abuse material. “As a technology company, we believe in an open and creative platform that has a positive impact on the world,” the Latitude team wrote.

“Explicit content involving descriptions or depictions of minors is inconsistent with this value, and we firmly oppose any content that may promote the sexual exploitation of minors. We have also received feedback from OpenAI, which asked us to implement changes.”

And by changes, they mean making the software’s output “consistent with OpenAI’s terms of service, which prohibit the display of harmful content.”

The biz clarified that its filter is designed to catch “content that is sexual or suggestive involving minors; child sexual abuse imagery; fantasy content (like ‘loli’) that depicts, encourages, or promotes the sexualization of minors or those who appear to be minors; or child sexual exploitation.”

And it added: “AI Dungeon will continue to support other NSFW content, including consensual adult content, violence, and profanity.”

[…]

it was also this week revealed programming blunders in AI Dungeon could be exploited to view the private adventures of other players. The pseudonymous AetherDevSecOps, who found and reported the flaws, used the holes to comb 188,000 adventures created between the AI and players from April 15 to 19, and saw that 46.3 per cent of them involved lewd role-playing, and about 31.4 per cent were pure pornographic.

[…]

disclosure on GitHub.

[…]

AI Dungeon’s makers were, we’re told, alerted to the API vulnerabilities on April 19. The flaws were addressed, and their details were publicly revealed this week by AetherDevSecOps.

Exploitation of the security shortcomings mainly involved abusing auto-incrementing ID numbers used in API calls, which are easy to enumerate to access data belonging to other players; no rate limits to mitigate this abuse; and a lack of monitoring for anomalous requests that could be malicious activity.

[…]

Community reaction

The introduction of the content filter sparked furor among fans. Some are angry that their free speech is under threat and that it ruins intimate game play with fictional consenting adults, some are miffed that they had no warning this was landing, others are shocked that child sex abuse material was being generated by the platform, and many are disappointed with the performance of the filter.

When it detects sensitive words, the game simply instead says the adventure “took a weird turn.” It appears to be triggered by obvious words relating to children, though the filter is spotty. An innocuous text input describing four watermelons, for example, upset the filter. A superhero rescuing a child was also censored.

Latitude admitted its experimental-grade software was not perfect, and repeated it wasn’t trying to censor all erotic consent – only material involving minors. It also said it will review blocked material to improve its code; given the above, that’s going to be a lot of reading.

[…]

The trick here is the wooden box located at the apex of the three copper pipes that make up the body of the lamp. [Peter] mounted rows of LEDs to the sides of the box that can be controlled with a switch on the bottom, which provides light in the absence of a traditional light bulb. The unmodified speaker goes inside the box, and connects to the audio wires that were run up one of the pipes.