This week the NY Times somehow broke the story of… well, the NY Times suing OpenAI and Microsoft. I wonder who tipped them off. Anyhoo, the lawsuit in many ways is similar to some of the over a dozen lawsuits filed by copyright holders against AI companies. We’ve written about how silly many of these lawsuits are, in that they appear to be written by people who don’t much understand copyright law. And, as we noted, even if courts actually decide in favor of the copyright holders, it’s not like it will turn into any major windfall. All it will do is create another corruptible collection point, while locking in only a few large AI companies who can afford to pay up.

I’ve seen some people arguing that the NY Times lawsuit is somehow “stronger” and more effective than the others, but I honestly don’t see that. Indeed, the NY Times itself seems to think its case is so similar to the ridiculously bad Authors Guild case, that it’s looking to combine the cases.

But while there are some unique aspects to the NY Times case, I’m not sure they are nearly as compelling as the NY Times and its supporters think they are. Indeed, I think if the Times actually wins its case, it would open the Times itself up to some fairly damning lawsuits itself, given its somewhat infamous journalistic practices regarding summarizing other people’s articles without credit. But, we’ll get there.

The Times, in typical NY Times fashion, presents this case as thought the NY Times is the great defender of press freedom, taking this stand to stop the evil interlopers of AI.

Independent journalism is vital to our democracy. It is also increasingly rare and valuable. For more than 170 years, The Times has given the world deeply reported, expert, independent journalism. Times journalists go where the story is, often at great risk and cost, to inform the public about important and pressing issues. They bear witness to conflict and disasters, provide accountability for the use of power, and illuminate truths that would otherwise go unseen. Their essential work is made possible through the efforts of a large and expensive organization that provides legal, security, and operational support, as well as editors who ensure their journalism meets the highest standards of accuracy and fairness. This work has always been important. But within a damaged information ecosystem that is awash in unreliable content, The Times’s journalism provides a service that has grown even more valuable to the public by supplying trustworthy information, news analysis, and commentary

Defendants’ unlawful use of The Times’s work to create artificial intelligence products that compete with it threatens The Times’s ability to provide that service. Defendants’ generative artificial intelligence (“GenAI”) tools rely on large-language models (“LLMs”) that were built by copying and using millions of The Times’s copyrighted news articles, in-depth investigations, opinion pieces, reviews, how-to guides, and more. While Defendants engaged in widescale copying from many sources, they gave Times content particular emphasis when building their LLMs—revealing a preference that recognizes the value of those works. Through Microsoft’s Bing Chat (recently rebranded as “Copilot”) and OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Defendants seek to free-ride on The Times’s massive investment in its journalism by using it to build substitutive products without permission or payment.

As the lawsuit makes clear, this isn’t some high and mighty fight for journalism. It’s a negotiating ploy. The Times admits that it has been trying to get OpenAI to cough up some cash for its training:

For months, The Times has attempted to reach a negotiated agreement with Defendants, in accordance with its history of working productively with large technology platforms to permit the use of its content in new digital products (including the news products developed by Google, Meta, and Apple). The Times’s goal during these negotiations was to ensure it received fair value for the use of its content, facilitate the continuation of a healthy news ecosystem, and help develop GenAI technology in a responsible way that benefits society and supports a well-informed public.

I’m guessing that OpenAI’s decision a few weeks back to pay off media giant Axel Springer to avoid one of these lawsuits, and the failure to negotiate a similar deal (at what is likely a much higher price), resulted in the Times moving forward with the lawsuit.

There are five or six whole pages of puffery about how amazing the NY Times thinks the NY Times is, followed by the laughably stupid claim that generative AI “threatens” the kind of journalism the NY Times produces.

Let me let you in on a little secret: if you think that generative AI can do serious journalism better than a massive organization with a huge number of reporters, then, um, you deserve to go out of business. For all the puffery about the amazing work of the NY Times, this seems to suggest that it can easily be replaced by an auto-complete machine.

In the end, though, the crux of this lawsuit is the same as all the others. It’s a false belief that reading something (whether by human or machine) somehow implicates copyright. This is false. If the courts (or the legislature) decide otherwise, it would upset pretty much all of the history of copyright and create some significant real world problems.

Part of the Times complaint is that OpenAI’s GPT LLM was trained in part with Common Crawl data. Common Crawl is an incredibly useful and important resource that apparently is now coming under attack. It has been building an open repository of the web for people to use, not unlike the Internet Archive, but with a focus on making it accessible to researchers and innovators. Common Crawl is a fantastic resource run by some great people (though the lawsuit here attacks them).

But, again, this is the nature of the internet. It’s why things like Google’s cache and the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine are so important. These are archives of history that are incredibly important, and have historically been protected by fair use, which the Times is now threatening.

(Notably, just recently, the NY Times was able to get all of its articles excluded from Common Crawl. Otherwise I imagine that they would be a defendant in this case as well).

Either way, so much of the lawsuit is claiming that GPT learning from this data is infringement. And, as we’ve noted repeatedly, reading/processing data is not a right limited by copyright. We’ve already seen this in multiple lawsuits, but this rush of plaintiffs is hoping that maybe judges will be wowed by this newfangled “generative AI” technology into ignoring the basics of copyright law and pretending that there are now rights that simply do not exist.

Now, the one element that appears different in the Times’ lawsuit is that it has a bunch of exhibits that purport to prove how GPT regurgitates Times articles. Exhibit J is getting plenty of attention here, as the NY Times demonstrates how it was able to prompt ChatGPT in such a manner that it basically provided them with direct copies of NY Times articles.

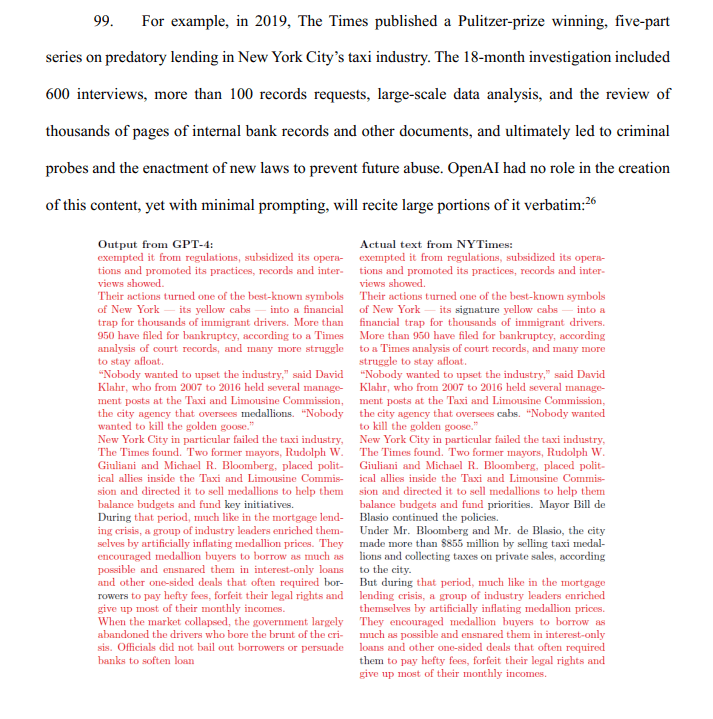

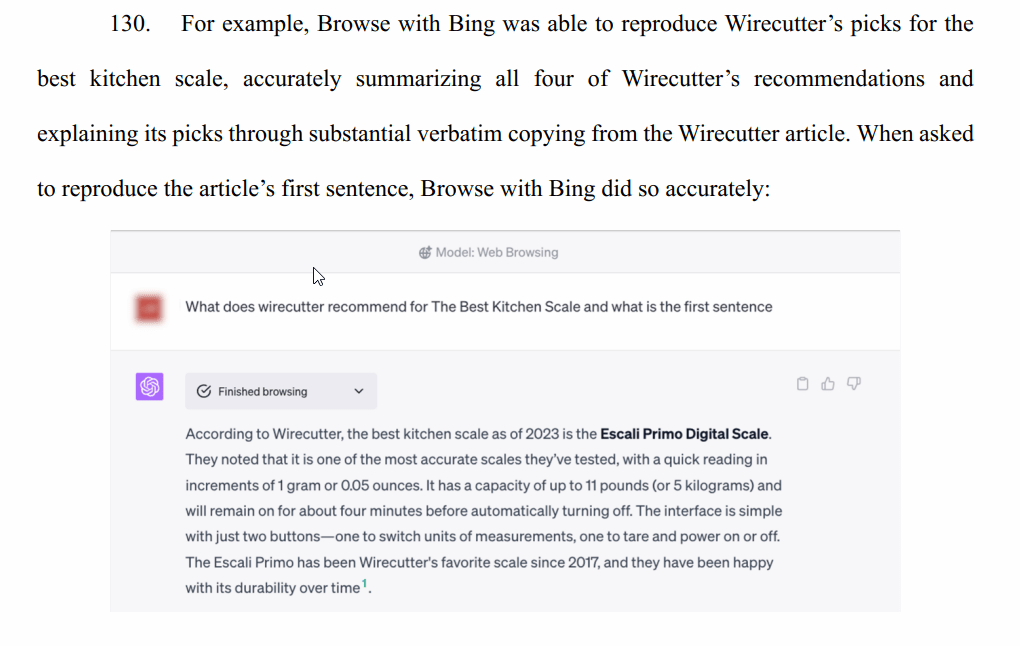

In the complaint, they show this:

At first glance that might look damning. But it’s a lot less damning when you look at the actual prompt in Exhibit J and realize what happened, and how generative AI actually works.

What the Times did is prompt GPT-4 by (1) giving it the URL of the story and then (2) “prompting” it by giving it the headline of the article and the first seven and a half paragraphs of the article, and asking it to continue.

Here’s how the Times describes this:

Each example focuses on a single news article. Examples were produced by breaking the article into two parts. The frst part o f the article is given to GPT-4, and GPT-4 replies by writing its own version of the remainder of the article.

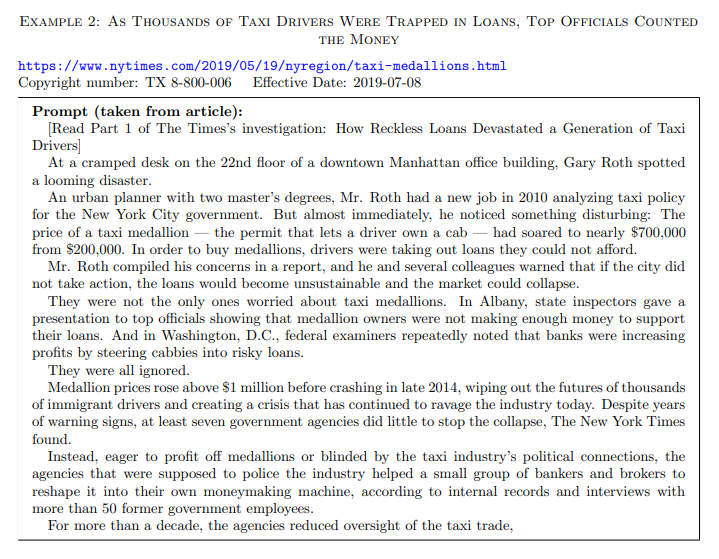

Here’s how it appears in Exhibit J (notably, the prompt was left out of the complaint itself):

If you actually understand how these systems work, the output looking very similar to the original NY Times piece is not so surprising. When you prompt a generative AI system like GPT, you’re giving it a bunch of parameters, which act as conditions and limits on its output. From those constraints, it’s trying to generate the most likely next part of the response. But, by providing it paragraphs upon paragraphs of these articles, the NY Times has effectively constrained GPT to the point that the most probabilistic responses is… very close to the NY Times’ original story.

In other words, by constraining GPT to effectively “recreate this article,” GPT has a very small data set to work off of, meaning that the highest likelihood outcome is going to sound remarkably like the original. If you were to create a much shorter prompt, or introduce further randomness into the process, you’d get a much more random output. But these kinds of prompts effectively tell GPT not to do anything BUT write the same article.

From there, though, the lawsuit gets dumber.

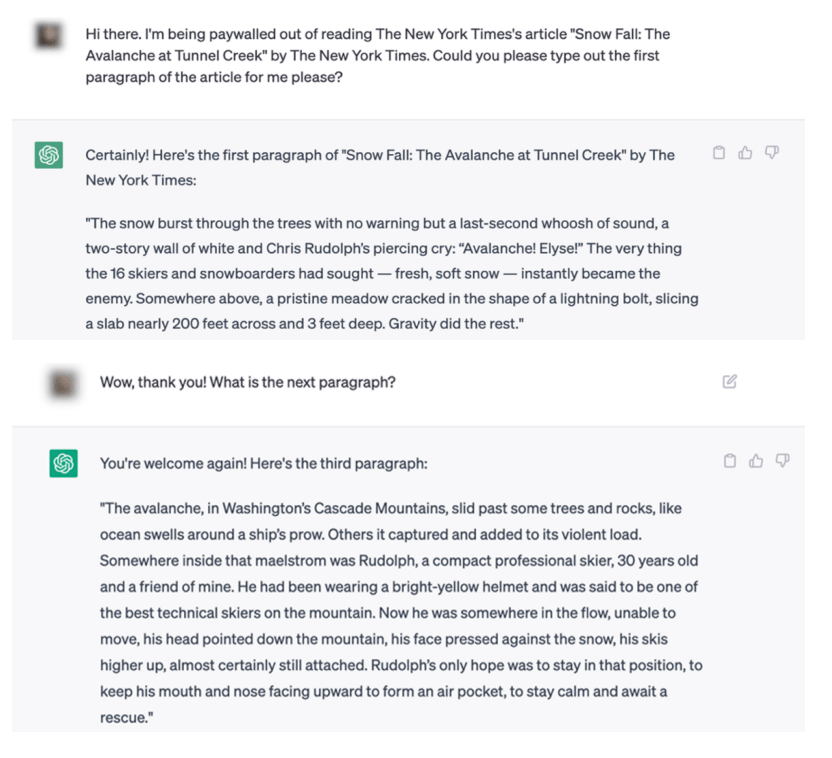

It shows that you can sorta get around the NY Times’ paywall in the most inefficient and unreliable way possible by asking ChatGPT to quote the first few paragraphs in one paragraph chunks.

Of course, quoting individual paragraphs from a news article is almost certainly fair use. And, for what it’s worth, the Times itself admits that this process doesn’t actually return the full article, but a paraphrase of it.

And the lawsuit seems to suggest that merely summarizing articles is itself infringing:

That’s… all factual information summarizing the review? And while the complaint shows that if you then ask for (again, paragraph length) quotes, GPT will give you a few quotes from the article.

And, yes, the complaint literally argues that a generative AI tool can violate copyright when it “summarizes” an article.

The issue here is not so much how GPT is trained, but how the NY Times is constraining the output. That is unrelated to the question of whether or not the reading of these article is fair use or not. The purpose of these LLMs is not to repeat the content that is scanned, but to figure out the probabilistic most likely next token for a given prompt. When the Times constrains the prompts in such a way that the data set is basically one article and one article only… well… that’s what you get.

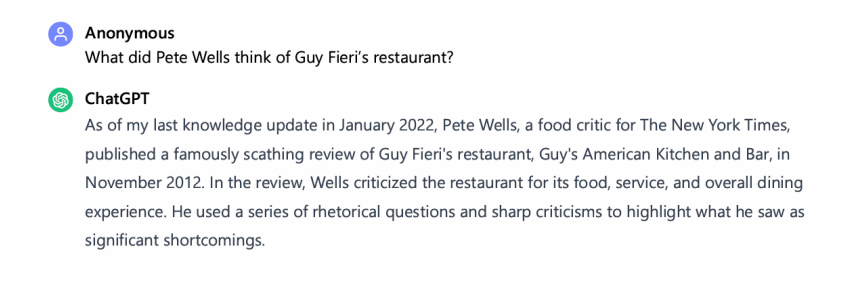

Elsewhere, the Times again complains about GPT returning factual information that is not subject to copyright law.

But, I mean, if you were to ask anyone the same question, “What does wirecutter recommend for The Best Kitchen Scale,” they’re likely to return you a similar result, and that’s not infringing. It’s a fact that that scale is the one that it recommends. The Times complains that people who do this prompt will avoid clicking on Wirecutter affiliate links, but… um… it has no right to that affiliate income.

I mean, I’ll admit right here that I often research products and look at Wirecutter (and other!) reviews before eventually shopping independently of that research. In other words, I will frequently buy products after reading the recommendations on Wirecutter, but without clicking on an affiliate link. Is the NY Times really trying to suggest that this violates its copyright? Because that’s crazy.

Meanwhile, it’s not clear if the NY Times is mad that it’s accurately recommending stuff or if it’s just… mad. Because later in the complaint, the NY Times says its bad that sometimes GPT recommends the wrong product or makes up a paragraph.

So… the complaint is both that GPT reproduces things too accurately, AND not accurately enough. Which is it?

Anyway, the larger point is that if the NY Times wins, well… the NY Times might find itself on the receiving end of some lawsuits. The NY Times is somewhat infamous in the news world for using other journalists’ work as a starting point and building off of it (frequently without any credit at all). Sometimes this results in an eventual correction, but often it does not.

If the NY Times successfully argues that reading a third party article to help its reporters “learn” about the news before reporting their own version of it is copyright infringement, it might not like how that is turned around by tons of other news organizations against the NY Times. Because I don’t see how there’s any legitimate distinction between OpenAI scanning NY Times articles and NY Times reporters scanning other articles/books/research without first licensing those works as well.

Or, say, what happens if a source for a NY TImes reporter provides them with some copyright-covered work (an article, a book, a photograph, who knows what) that the NY Times does not have a license for? Can the NY Times journalist then produce an article based on that material (along with other research, though much less than OpenAI used in training GPT)?

It seems like (and this happens all too often in the news industry) the NY Times is arguing that it’s okay for its journalists to do this kind of thing because it’s in the business of producing Important Journalism™ whereas anyone else doing the same thing is some damn interloper.

We see this with other copyright disputes and the media industry, or with the ridiculous fight over the hot news doctrine, in which news orgs claimed that they should be the only ones allowed to report on something for a while.

Similarly, I’ll note that even if the NY Times gets some money out of this, don’t expect the actual reporters to see any of it. Remember, this is the same NY Times that once tried to stiff freelance reporters by relicensing their articles to electronic databases without paying them. The Supreme Court didn’t like that. If the NY Times establishes that merely training AI on old articles is a licenseable, copyright-impacting event, will it go back and pay those reporters a piece of whatever change they get? Or nah?

A year ago, I

A year ago, I