Science fiction has whetted our imagination for helpful voice assistants. Whether it’s JARVIS from Iron Man, KITT from Knight Rider, or Computer from Star Trek, many of us harbor a desire for a voice assistant to manage the minutiae of our daily lives. Speech recognition and voice technologies have advanced rapidly in recent years, particularly with the adoption of Siri, Alexa, and Google Home.

However, many in the maker community are concerned — rightly — about the privacy implications of using commercial solutions. Just how much data do you give away every time you speak with a proprietary voice assistant? Just what are they storing in the cloud? What free, private, and open source options are available? Is it possible to have a voice stack that doesn’t share data across the internet?

Yes, it is. In this article, I’ll walk you through the options.

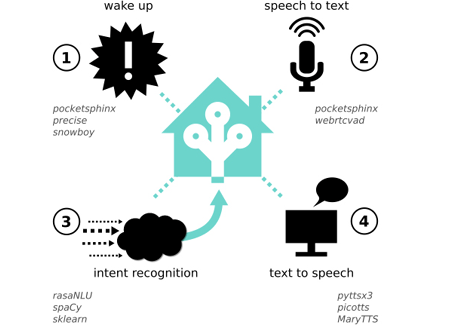

WHAT’S IN A VOICE STACK?

Some voice assistants offer a whole stack of software, but you may prefer to pick and choose which layers to use.

» WAKE WORD SPOTTER — This layer is constantly listening until it hears the wake word or hot word, at which point it will activate the speech-to-text layer. “Alexa,” “Jarvis,” and “OK Google” are wake words you may know.

» SPEECH TO TEXT (STT) — Also called automatic speech recognition (ASR). Once activated by the wake word, the job of the STT layer is just that: to recognize what you’re saying and turn it into written form. Your spoken phrase is called an utterance.

» INTENT PARSER — Also called natural language processing (NLP) or natural language understanding (NLU). The job of this layer is to take the text from STT and determine what action you would like to take. It often does this by recognizing entities — such as a time, date, or object — in the utterance.

» SKILL — Once the intent parser has determined what you’d like to do, an application or handler is triggered. This is usually called a skill or application. The computer may also create a reply in human-readable language, using natural language generation (NLG).

» TEXT TO SPEECH — Once the skill has completed its task, the voice assistant may acknowledge or respond using a synthesized voice.

Some layers work on device, meaning they don’t need an internet connection. These are a good option for those concerned about privacy, because they don’t share your data across the internet. Others do require an internet connection because they offload processing to cloud servers; these can be more of a privacy risk.

Before you pick a voice stack for your project you’ll need to ask key questions such as:

• What’s the interface of the software like — how easy is it to install and configure, and what support is available?

• What sort of assurances do you have around the software? How accurate is it? Does it recognize your accent well? Is it well tested? Does it make the right decisions about your intended actions?

• What sort of context, or use case, do you have? Do you want your data going across the internet or being stored on cloud servers? Is your hardware constrained in terms of memory or CPU? Do you need to support languages other than English?

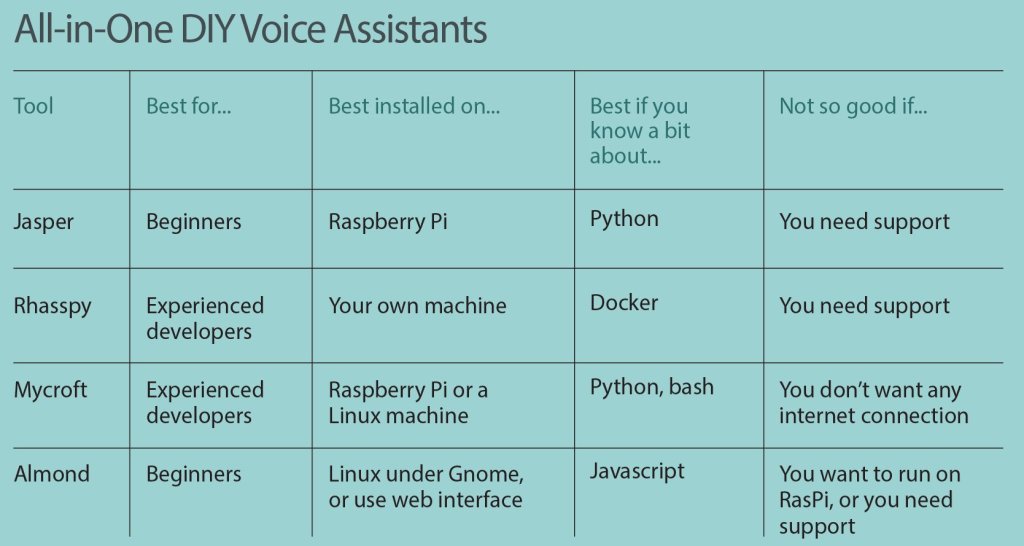

ALL-IN-ONE VOICE SOLUTIONS

If you’re looking for an easy option to start with, you might want to try an all-in-one voice solution. These products often package other software together in a way that’s easy to install. They’ll get your DIY voice project up and running the fastest.

Jasper is designed from the ground up for makers, and is intended to run on a Raspberry Pi. It’s a great first step for integrating voice into your projects. With Jasper, you choose which software components you want to use, and write your own skills, and it’s possible to configure it so that it doesn’t need an internet connection to function.

Rhasspy also uses a modular framework and can be run without an internet connection. It’s designed to run under Docker and has integrations for NodeRED and for Home Assistant, a popular open source home automation software.

Mycroft is modular too, but by default it requires an internet connection. Skills in Mycroft are easy to develop and are written in Python 3; existing skills include integrations with Home Assistant and Mozilla WebThings. Mycroft also builds open-source hardware voice assistants similar to Amazon Echo and Google Home. And it has a distribution called Picroft specifically for the Raspberry Pi 3B and above.

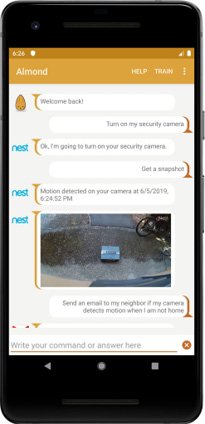

Almond is a privacy-preserving voice assistant from Stanford that’s available as a web app, for Android, or for the GNOME Linux desktop. Almond is very new on the scene, but already has an integration with Home Assistant. It also has options that allow it to run on the command line, so it could be installed on a Raspberry Pi (with some effort).

The languages supported by all-in-one voice solutions are dependent on what software options are selected, but by default they use English. Other languages require additional configuration.

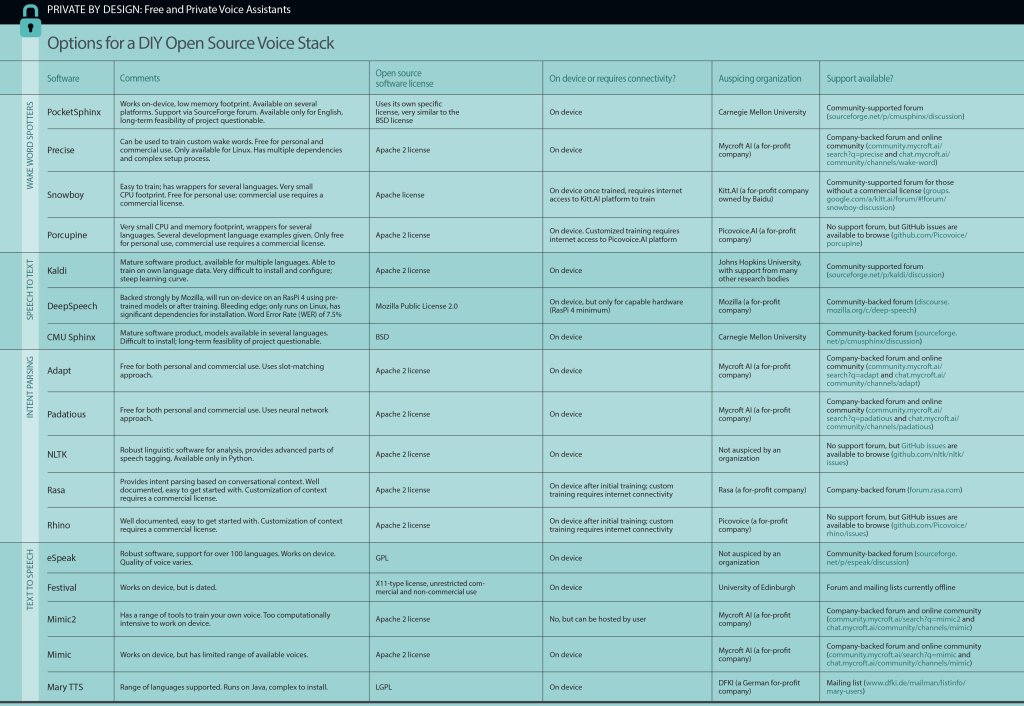

WAKE WORD SPOTTERS

PocketSphinx is a great option for wake word spotting. It’s available for Linux, Mac, Windows platforms, as well as Android and iOS; however, installation can be involved. PocketSphinx works on-device, by recognizing phonemes, which are the smallest units of sound that make up a word.

For example, hello and world each have four phonemes:

hello H EH L OW

world W ER L D

The downside of PocketSphinx is that its core developers appear to have moved on to a for-profit company, so it’s not clear how long PocketSphinx or its parent CMU Sphinx will be around.

Precise by Mycroft.AI uses a recurrent neural network to learn what are and are not wake words. You can train your own wake words with Precise, but it does take a lot of training to get accurate results.

Snowboy is free for makers to train your own wake word, using Kitt.AI’s (proprietary) training, but also comes with several pre-trained models, and wrappers for several programming languages including Python and Go. Once you’ve got your trained wake word, you no longer need an internet connection. It’s an easier option for beginners than Precise or PocketSphinx, and has a very small CPU footprint, which makes it ideal for embedded electronics. Kitt.AI was acquired by Chinese giant Baidu in 2017, although to date it appears to remain as its own entity.

Porcupine from Picovoice is designed specifically for embedded applications. It comes in two variants: a complete model with higher accuracy, and a compressed model with slightly lower accuracy but a much smaller CPU and memory footprint. It provides examples for integration with several common programming languages. Ada, the voice assistant recently released by Home Assistant, uses Porcupine under the hood.

SPEECH TO TEXT

Kaldi has for years been the go-to open source speech-to-text engine. Models are available for several languages, including Mandarin. It works on-device but is notoriously difficult to set up, not recommended for beginners. You can use Kaldi to train your own speech-to-text model, if you have spoken phrases and recordings, for example in another language. Researchers in the Australian Centre for the Dynamics of Language have recently developed Elpis , a wrapper for Kaldi that makes transcription to text a lot easier. It’s aimed at linguists who need to transcribe lots of recordings.

CMU Sphinx , like its child PocketSphinx, is based on phoneme recognition, works on-device, and is complex for beginners.

DeepSpeech, part of Mozilla’s Common Voice project , is another major player in the open source space that’s been gaining momentum. DeepSpeech comes with a pre-trained English model but can be trained on other data sets — this requires a compatible GPU. Trained models can be exported using TensorFlow Lite for inference, and it’s been tested on an RasPi 4, where it comfortably performs real-time transcriptions. Again, it’s complex for beginners.

INTENT PARSING AND ENTITY RECOGNITION

There are two general approaches to intent parsing and entity recognition: neural networks and slot matching. The neural network is trained on a set of phrases, and can usually match an utterance that “sounds like” an intent that should trigger an action. In the slot matching approach, your utterance needs to closely match a set of predefined “slots,” such as “play the song [songname] using [streaming service].” If you say “play Blur,” the utterance won’t match the intent.

Padatious is Mycroft’s new intent parser, which uses a neural network. They also developed Adapt which uses the slot matching approach.

For those who use Python and want to dig a little deeper into the structure of language, the Natural Language Toolkit is a powerful tool, and can do “parts of speech” tagging — for example recognizing the names of places.

Rasa is a set of tools for conversational applications, such as chatbots, and includes a robust intent parser. Rasa makes predictions about intent based on the entire context of a conversation. Rasa also has a training tool called Rasa X, which helps you train the conversational agent to your particular context. Rasa X comes in both an open source community edition and a licensed enterprise edition.

Picovoice also has Rhino, which comes with pre-trained intent parsing models for free. However, customization of models — for specific contexts like medical or industrial applications — requires a commercial license.

TEXT TO SPEECH

Just like speech-to-text models need to be “trained” for a particular language or dialect, so too do text-to-speech models. However, text to speech is usually trained on a single voice, such as “British Male” or “American Female.”

eSpeak is perhaps the best-known open source text-to-speech engine. It supports over 100 languages and accents, although the quality of the voice varies between languages. eSpeak supports the Speech Synthesis Markup Language format, which can be used to add inflection and emphasis to spoken language. It is available for Linux, Windows, Mac, and Android systems, and it works on-device, so it can be used without an internet connection, making it ideal for maker projects.

Festival is now quite dated, and needs to be compiled from source for Linux, but does have around 15 American English voices available. It works on-device. It’s mentioned here out of respect; for over a decade it was considered the premier open source text-to-speech engine.

Mimic2 is a Tacotron fork from Mycroft AI, who have also released the to allow you to build your own text-to-speech voices. To get a high-quality voice requires up to 100 hours of “clean” speech, and Mimic2 is too large to work on-device, so you need to host it on your own server or connect your device to the Mycroft Mimic2 server. Currently it only has a pre-trained voice for American English.

Mycroft’s earlier Mimic TTS can work on-device, even on a Raspberry Pi, and is another good candidate for maker projects. It’s a fork of CMU Flite.

Mary Text to Speech supports several, mainly European languages, and has tools for synthesizing new voices. It runs on Java, so can be complex to install.

So, that’s a map of the current landscape in open source voice assistants and software layers. You can compare all these layers in the chart at the end of this article. Whatever your voice project, you’re likely to find something here that will do the job well — and will keep your voice and your data private from Big Tech.

WHAT’S NEXT FOR OPEN SOURCE VOICE?

As machine learning and natural language processing continue to advance rapidly, we’ve seen the decline of the major open source voice tools. CMU Sphinx, Festival, and eSpeak have become outdated as their supporters have adopted other tools, or maintainers have gone into private industry and startups.

We’re going to see more software that’s free for personal use but requires a commercial license for enterprise, as Rasa and Picovoice do today. And it’s understandable; dealing with voice in an era of machine learning is data intensive, a poor fit for the open source model of volunteer development. Instead, companies are driven to commercialize by monetizing a centralized “platform as a service.”

Another trajectory this might take is some form of value exchange. Training all those neural networks and machine learning models — for STT, intent parsing, and TTS — takes vast volumes of data. More companies may provide software on an open source basis and in return ask users to donate voice samples to improve the data sets.Mozilla’s Common Voice follows this model.

Another trend is voice moving on-device. The newer, machine-learning-driven speech tools originally were too computationally intensive to run on low-end hardware like the Raspberry Pi. But with DeepSpeech now running on a RasPi 4, it’s only a matter of time before the newer TTS tools can too.

We’re also seeing a stronger focus on personalization, with the ability to customize both speech-to-text and text-to-speech software.

WHAT WE STILL NEED

What’s lacking across all these open source tools are user-friendly interfaces to capture recordings and train models. Open source products must continue to improve their UIs to attract both developer and user communities; failure to do so will see more widespread adoption of proprietary and “freemium” tools.

As always in emerging technologies, standards remain elusive. For example, skills have to be rewritten for different voice assistants. Device manufacturers, particularly for smart home appliances, won’t want to develop and maintain integrations for multiple assistants; much of this will fall to an already-stretched open source community until mechanisms for interoperability are found. Mozilla’s WebThings ecosystem (see page 50) may plug the interoperability gap if it can garner enough developer support.

Regardless, the burden rests with the open source community to find ways to connect to proprietary systems (see page 46 for a fun example) because there’s no incentive for manufacturers to do the converse.

The future of open source rests in your hands! Experiment and provide feedback, issues, pull requests, data, ideas, and bugs. With your help, open source can continue to have a strong voice.

click the image to view full size. Alternatively, you can download this data as a spreadsheet by clicking here.