A study led by University of Toronto researchers, published today in the American Heart Association journal Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging, found that blood pressure can be measured accurately by taking a quick video selfie.

Kang Lee, a professor of applied psychology and human development at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education and Canada Research Chair in developmental neuroscience, was the lead author of the study, working alongside researchers from the Faculty of Medicine’s department of physiology, and from Hangzhou Normal University and Zhejiang Normal University in China.

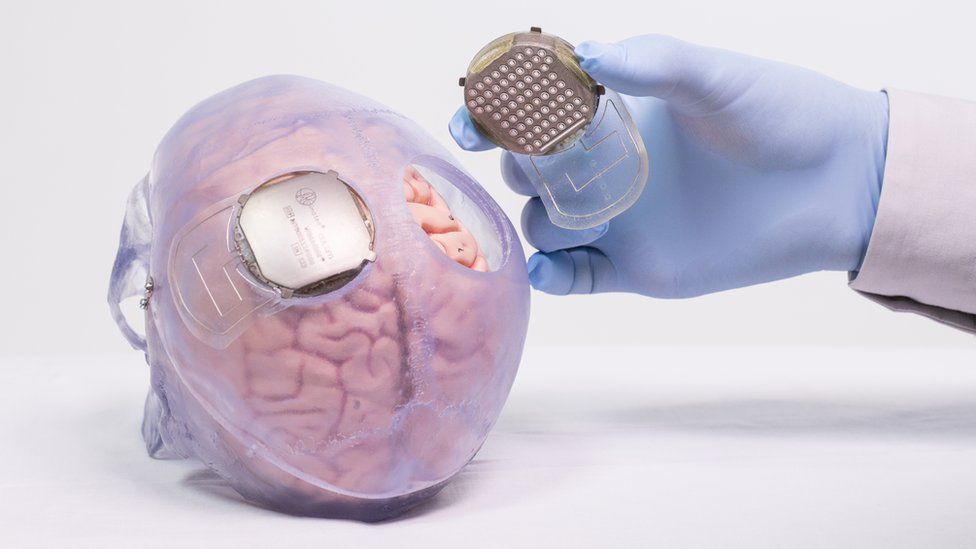

Using a technology co-discovered by Lee and his postdoctoral researcher Paul Zheng called transdermal optical imaging, researchers measured the blood pressure of 1,328 Canadian and Chinese adults by capturing two-minute videos of their faces on an iPhone. Results were compared to standard devices used to measure blood pressure.

The researchers found they were able to measure three types of blood pressure with 95 to 96 per cent accuracy.

[…]

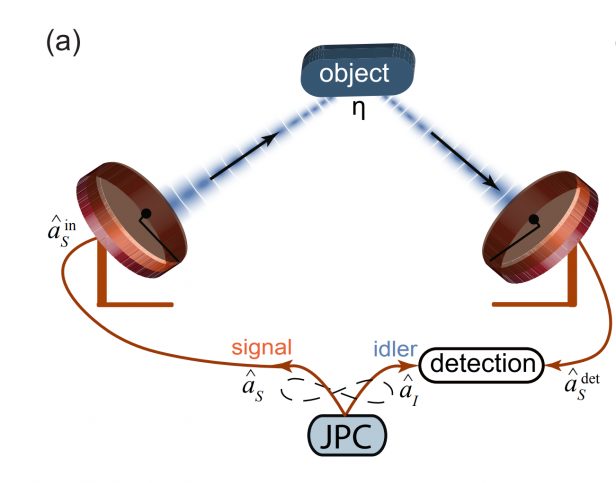

Transdermal optical imaging works by capitalizing on the translucent nature of facial skin. When the light reaches the face, it penetrates the skin and reaches hemoglobin underneath it, which is red. This technology uses the optical sensor on a smartphone to capture the reflected red light from hemoglobin, which allows the technology to visualize and measure blood flow changes under the skin.

“From the video captured by the technology, you can see how the blood flows in different parts of the face and through this ebb and flow of blood in the face, you can get a lot of information,” says Lee.

He understood that the transdermal optical imaging technology had significant practical implications, so, with the help of U of T and MaRS, he formed a startup company called Nuralogix alongside entrepreneur Marzio Pozzuoli, who is now the CEO.

[…]

Nuralogix has developed a smartphone app called Anura that allows people to try out the transdermal optical imaging software for themselves. In the publicly available version of the app, people can record a 30-second video of their face and will receive measurements for stress levels and resting heart rate. In the fall, the company will release a version of the app in China that includes blood pressure measurements.

Lee says there is more research to be done to ensure that health measurements using transdermal optical imaging are as accurate as possible. In the recent study, for example, only people with regular or slightly higher blood pressure were measured. The study sample also did not have people with very dark or very fair skin. More diverse research subjects will make measurements more accurate, says Lee, but there are challenges when looking for people with very high and low blood pressure.

“In order to improve our app to make it usable, particularly for people with hypertension, we need to collect a lot of data from them, which is very, very hard because a lot of them are already taking medicine,” says Lee. “Ethically, we cannot tell them not to take medicine, but from time to time, we get participants who do not take medicine so we can get hypertensive and hypotensive people this way.”

While there are a wide range of applications for transdermal optical imaging technology, Lee says data privacy is of utmost concern. He says when a person uses the software by recording a video of their face, only the results are uploaded to the cloud but the video is not.

“We only extract blood flow information from your face and send that to the cloud. So from the cloud, if I look at your blood flow, I couldn’t tell it is you,” he says.

[…]

The research team also hopes to expand the capabilities of the technology to measure other health markers, including blood-glucose levels, hemoglobin and cholesterol.

Nuralogix plans on monetizing the technology by making an app that allows consumers to pay a low monthly fee to access more detailed health data. They are also licensing the technology through a product called DeepAffex, a cloud-based AI engine that can be used by businesses who are interested in the transdermal optical imaging technology in a range of industries from health care to security.