Whether we like it or not, we all use the cloud to communicate and to store and process our data. We use dozens of cloud services, sometimes indirectly and unwittingly. We do so because the cloud brings real benefits to individuals and organizations alike. We can access our data across multiple devices, communicate with anyone from anywhere, and command a remote data center’s worth of power from a handheld device.

But using the cloud means our security and privacy now depend on cloud providers. Remember: the cloud is just another way of saying “someone else’s computer.” Cloud providers are single points of failure and prime targets for hackers to scoop up everything from proprietary corporate communications to our personal photo albums and financial documents.

The risks we face from the cloud today are not an accident. For Google to show you your work emails, it has to store many copies across many servers. Even if they’re stored in encrypted form, Google must decrypt them to display your inbox on a webpage. When Zoom coordinates a call, its servers receive and then retransmit the video and audio of all the participants, learning who’s talking and what’s said. For Apple to analyze and share your photo album, it must be able to access your photos.

Hacks of cloud services happen so often that it’s hard to keep up. Breaches can be so large as to affect nearly every person in the country, as in the Equifax breach of 2017, or a large fraction of the Fortune 500 and the U.S. government, as in the SolarWinds breach of 2019-20.

It’s not just attackers we have to worry about. Some companies use their access—benefiting from weak laws, complex software, and lax oversight—to mine and sell our data.

[…]

The less someone knows, the less they can put you and your data at risk. In security this is called Least Privilege. The decoupling principle applies that idea to cloud services by making sure systems know as little as possible while doing their jobs. It states that we gain security and privacy by separating private data that today is unnecessarily concentrated.

To unpack that a bit, consider the three primary modes for working with our data as we use cloud services: data in motion, data at rest, and data in use. We should decouple them all.

Our data is in motion as we exchange traffic with cloud services such as videoconferencing servers, remote file-storage systems, and other content-delivery networks. Our data at rest, while sometimes on individual devices, is usually stored or backed up in the cloud, governed by cloud provider services and policies. And many services use the cloud to do extensive processing on our data, sometimes without our consent or knowledge. Most services involve more than one of these modes.

[…]

Cryptographer David Chaum first applied the decoupling approach in security protocols for anonymity and digital cash in the 1980s, long before the advent of online banking or cryptocurrencies. Chaum asked: how can a bank or a network service provider provide a service to its users without spying on them while doing so?

Chaum’s ideas included sending Internet traffic through multiple servers run by different organizations and divvying up the data so that a breach of any one node reveals minimal information about users or usage. Although these ideas have been influential, they have found only niche uses, such as in the popular Tor browser.

Trust, but Don’t Identify

The decoupling principle can protect the privacy of data in motion, such as financial transactions and Web browsing patterns that currently are wide open to vendors, banks, websites, and Internet Service Providers (ISPs).

STORYTK

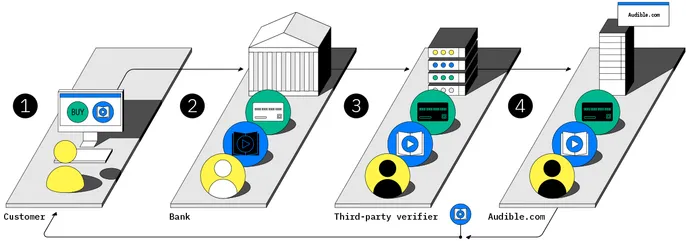

1. Barath orders Bruce’s audiobook from Audible. 2. His bank does not know what he is buying, but it guarantees the payment. 3. A third party decrypts the order details but does not know who placed the order. 4. Audible delivers the audiobook and receives the payment.

DECOUPLED E-COMMERCE: By inserting an independent verifier between the bank and the seller and by blinding the buyer’s identity from the verifier, the seller and the verifier cannot identify the buyer, and the bank cannot identify the product purchased. But all parties can trust that the signed payment is valid.

STORYTK

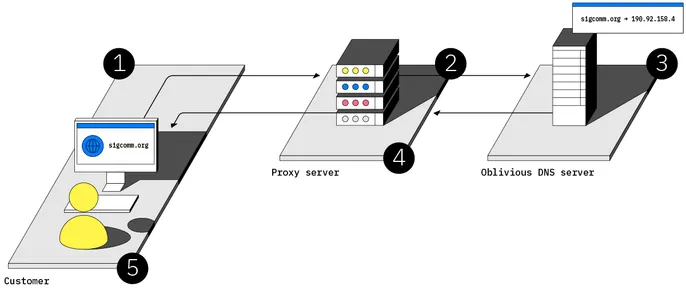

1. Bruce’s browser sends a doubly encrypted request for the IP address of sigcomm.org. 2. A third-party proxy server decrypts one layer and passes on the request, replacing Bruce’s identity with an anonymous ID. 3. An Oblivious DNS server decrypts the request, looks up the IP address, and sends it back in an encrypted reply. 4. The proxy server forwards the encrypted reply to Bruce’s browser. 5. Bruce’s browser decrypts the response to obtain the IP address of sigcomm.org.

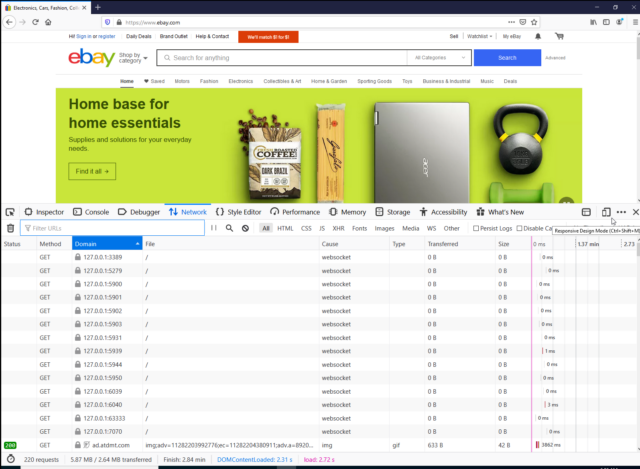

DECOUPLED WEB BROWSING: ISPs can track which websites their users visit because requests to the Domain Name System (DNS), which converts domain names to IP addresses, are unencrypted. A new protocol called Oblivious DNS can protect users’ browsing requests from third parties. Each name-resolution request is encrypted twice and then sent to an intermediary (a “proxy”) that strips out the user’s IP address and decrypts the outer layer before passing the request to a domain name server, which then decrypts the actual request. Neither the ISP nor any other computer along the way can see what name is being queried. The Oblivious resolver has the key needed to decrypt the request but no information about who placed it. The resolver encrypts its reply so that only the user can read it.

Similar methods have been extended beyond DNS to multiparty-relay protocols that protect the privacy of all Web browsing through free services such as Tor and subscription services such as INVISV Relay and Apple’s iCloud Private Relay.

[…]

Meetings that were once held in a private conference room are now happening in the cloud, and third parties like Zoom see it all: who, what, when, where. There’s no reason a videoconferencing company has to learn such sensitive information about every organization it provides services to. But that’s the way it works today, and we’ve all become used to it.

There are multiple threats to the security of that Zoom call. A Zoom employee could go rogue and snoop on calls. Zoom could spy on calls of other companies or harvest and sell user data to data brokers. It could use your personal data to train its AI models. And even if Zoom and all its employees are completely trustworthy, the risk of Zoom getting breached is omnipresent. Whatever Zoom can do with your data in motion, a hacker can do to that same data in a breach. Decoupling data in motion could address those threats.

[…]

Most storage and database providers started encrypting data on disk years ago, but that’s not enough to ensure security. In most cases, the data is decrypted every time it is read from disk. A hacker or malicious insider silently snooping at the cloud provider could thus intercept your data despite it having been encrypted.

Cloud-storage companies have at various times harvested user data for AI training or to sell targeted ads. Some hoard it and offer paid access back to us or just sell it wholesale to data brokers. Even the best corporate stewards of our data are getting into the advertising game, and the decade-old feudal model of security—where a single company provides users with hardware, software, and a variety of local and cloud services—is breaking down.

Decoupling can help us retain the benefits of cloud storage while keeping our data secure. As with data in motion, the risks begin with access the provider has to raw data (or that hackers gain in a breach). End-to-end encryption, with the end user holding the keys, ensures that the cloud provider can’t independently decrypt data from disk.

[…]

Modern protocols for decoupled data storage, like Tim Berners-Lee’s Solid, provide this sort of security. Solid is a protocol for distributed personal data stores, called pods. By giving users control over both where their pod is located and who has access to the data within it—at a fine-grained level—Solid ensures that data is under user control even if the hosting provider or app developer goes rogue or has a breach. In this model, users and organizations can manage their own risk as they see fit, sharing only the data necessary for each particular use.

[…]

the last few years have seen the advent of general-purpose, hardware-enabled secure computation. This is powered by special functionality on processors known as trusted execution environments (TEEs) or secure enclaves. TEEs decouple who runs the chip (a cloud provider, such as Microsoft Azure) from who secures the chip (a processor vendor, such as Intel) and from who controls the data being used in the computation (the customer or user). A TEE can keep the cloud provider from seeing what is being computed. The results of a computation are sent via a secure tunnel out of the enclave or encrypted and stored. A TEE can also generate a signed attestation that it actually ran the code that the customer wanted to run.

With TEEs in the cloud, the final piece of the decoupling puzzle drops into place. An organization can keep and share its data securely at rest, move it securely in motion, and decrypt and analyze it in a TEE such that the cloud provider doesn’t have access. Once the computation is done, the results can be reencrypted and shipped off to storage. CPU-based TEEs are now widely available among cloud providers, and soon GPU-based TEEs—useful for AI applications—will be common as well.

[…]

Decoupling also allows us to look at security more holistically. For example, we can dispense with the distinction between security and privacy. Historically, privacy meant freedom from observation, usually for an individual person. Security, on the other hand, was about keeping an organization’s data safe and preventing an adversary from doing bad things to its resources or infrastructure.

There are still rare instances where security and privacy differ, but organizations and individuals are now using the same cloud services and facing similar threats. Security and privacy have converged, and we can usefully think about them together as we apply decoupling.

[…]

Decoupling isn’t a panacea. There will always be new, clever side-channel attacks. And most decoupling solutions assume a degree of noncollusion between independent companies or organizations. But that noncollusion is already an implicit assumption today: we trust that Google and Advanced Micro Devices will not conspire to break the security of the TEEs they deploy, for example, because the reputational harm from being found out would hurt their businesses. The primary risk, real but also often overstated, is if a government secretly compels companies to introduce backdoors into their systems. In an age of international cloud services, this would be hard to conceal and would cause irreparable harm.

[…]

Imagine that individuals and organizations held their credit data in cloud-hosted repositories that enable fine-grained encryption and access control. Applying for a loan could then take advantage of all three modes of decoupling. First, the user could employ Solid or a similar technology to grant access to Equifax and a bank only for the specific loan application. Second, the communications to and from secure enclaves in the cloud could be decoupled and secured to conceal who is requesting the credit analysis and the identity of the loan applicant. Third, computations by a credit-analysis algorithm could run in a TEE. The user could use an external auditor to confirm that only that specific algorithm was run. The credit-scoring algorithm might be proprietary, and that’s fine: in this approach, Equifax doesn’t need to reveal it to the user, just as the user doesn’t need to give Equifax access to unencrypted data outside of a TEE.

Building this is easier said than done, of course. But it’s practical today, using widely available technologies. The barriers are more economic than technical.

[…]

One of the challenges of trying to regulate tech is that industry incumbents push for tech-only approaches that simply whitewash bad practices. For example, when Facebook rolls out “privacy-enhancing” advertising, but still collects every move you make, has control of all the data you put on its platform, and is embedded in nearly every website you visit, that privacy technology does little to protect you. We need to think beyond minor, superficial fixes.

Decoupling might seem strange at first, but it’s built on familiar ideas. Computing’s main tricks are abstraction and indirection. Abstraction involves hiding the messy details of something inside a nice clean package: when you use Gmail, you don’t have to think about the hundreds of thousands of Google servers that have stored or processed your data. Indirection involves creating a new intermediary between two existing things, such as when Uber wedged its app between passengers and drivers.

The cloud as we know it today is born of three decades of increasing abstraction and indirection. Communications, storage, and compute infrastructure for a typical company were once run on a server in a closet. Next, companies no longer had to maintain a server closet, but could rent a spot in a dedicated colocation facility. After that, colocation facilities decided to rent out their own servers to companies. Then, with virtualization software, companies could get the illusion of having a server while actually just running a virtual machine on a server they rented somewhere. Finally, with serverless computing and most types of software as a service, we no longer know or care where or how software runs in the cloud, just that it does what we need it to do.

[…]

We’re now at a turning point where we can add further abstraction and indirection to improve security, turning the tables on the cloud providers and taking back control as organizations and individuals while still benefiting from what they do.

The needed protocols and infrastructure exist, and there are services that can do all of this already, without sacrificing the performance, quality, and usability of conventional cloud services.

But we cannot just rely on industry to take care of this. Self-regulation is a time-honored stall tactic: a piecemeal or superficial tech-only approach would likely undermine the will of the public and regulators to take action. We need a belt-and-suspenders strategy, with government policy that mandates decoupling-based best practices, a tech sector that implements this architecture, and public awareness of both the need for and the benefits of this better way forward.

Source: Essays: Decoupling for Security – Schneier on Security