I’ve used a Samsung Galaxy smartphone almost every day for nearly 4 years. I used them because Samsung had fantastic hardware that was matched by (usually) excellent software. But in 2020, a Samsung phone is no longer my daily driver, and there’s one simple reason that’s the case: Ads.

Ads Everywhere

Ads in Samsung phones never really bothered me, at least not until the past few months. It started with the Galaxy Z Flip. A tweet from Todd Haselton of CNBC, embedded below, is what really caught my eye. Samsung had put an ad from DirectTV in the stock dialer app. This is really something I never would have expected from any smartphone company, let alone Samsung.

It showed up in the “Places” tab in the dialer app, which is in partnership with Yelp and lets you search for different businesses directly from the dialer app so you don’t need to Google somewhere to find the address or phone number. I looked into it, to see if this was maybe a mistake on Yelp’s part, accidentally displaying an ad where it shouldn’t have, but nope. The ad was placed by Samsung, in an area where it could blend in so they could make money.

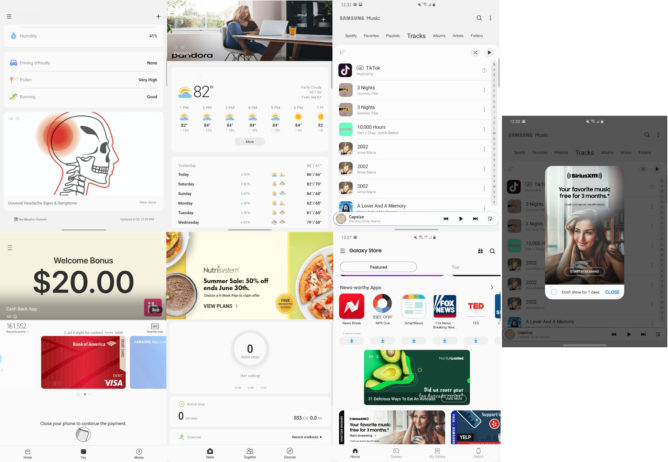

Similar ads exist throughout a bunch of Samsung apps. Samsung Music has ads that look like another track in your library. Samsung Health and Samsung Pay have banners for promotional ads. The stock weather app has ads that look like they could be news. There is also more often very blatant advertising in most of these apps as well.

Samsung Music will give you a popup ad for Sirius XM, even though Spotify is built into the Samsung Music app. You can hide the SiriusXM popup, but only for 7 days at a time. A week later, it will be right back there waiting for you. Samsung will also give you push notification ads for new products from Bixby, Samsung Pay, and Samsung Push Service.

If you’re wondering which Samsung apps have ads, I’ve listed all the ones I’ve seen ads in and ad-less alternatives to them below.

Why are there even ads in the first place?

To really understand Samsung’s absurd and terrible advertising on its smartphones, you have to understand why big companies advertise. Google advertises because its “free services” still cost money to provide. The ads they serve you in Google services help cover the cost of that 15GB of storage, Google Voice phone number, unlimited Google Photos storage, and whatnot. That’s all to say there is a reason for it, you are getting something in return for those ads.

Websites and YouTube channels serve ads because the content they are providing to you for free is not free for them to make. They need to be compensated for what they are providing to you for free. Again, you are getting something for free, and serving you an ad acts as a form of payment. There was no purchase of a product, hardware or software, for you to have access to their content and services.

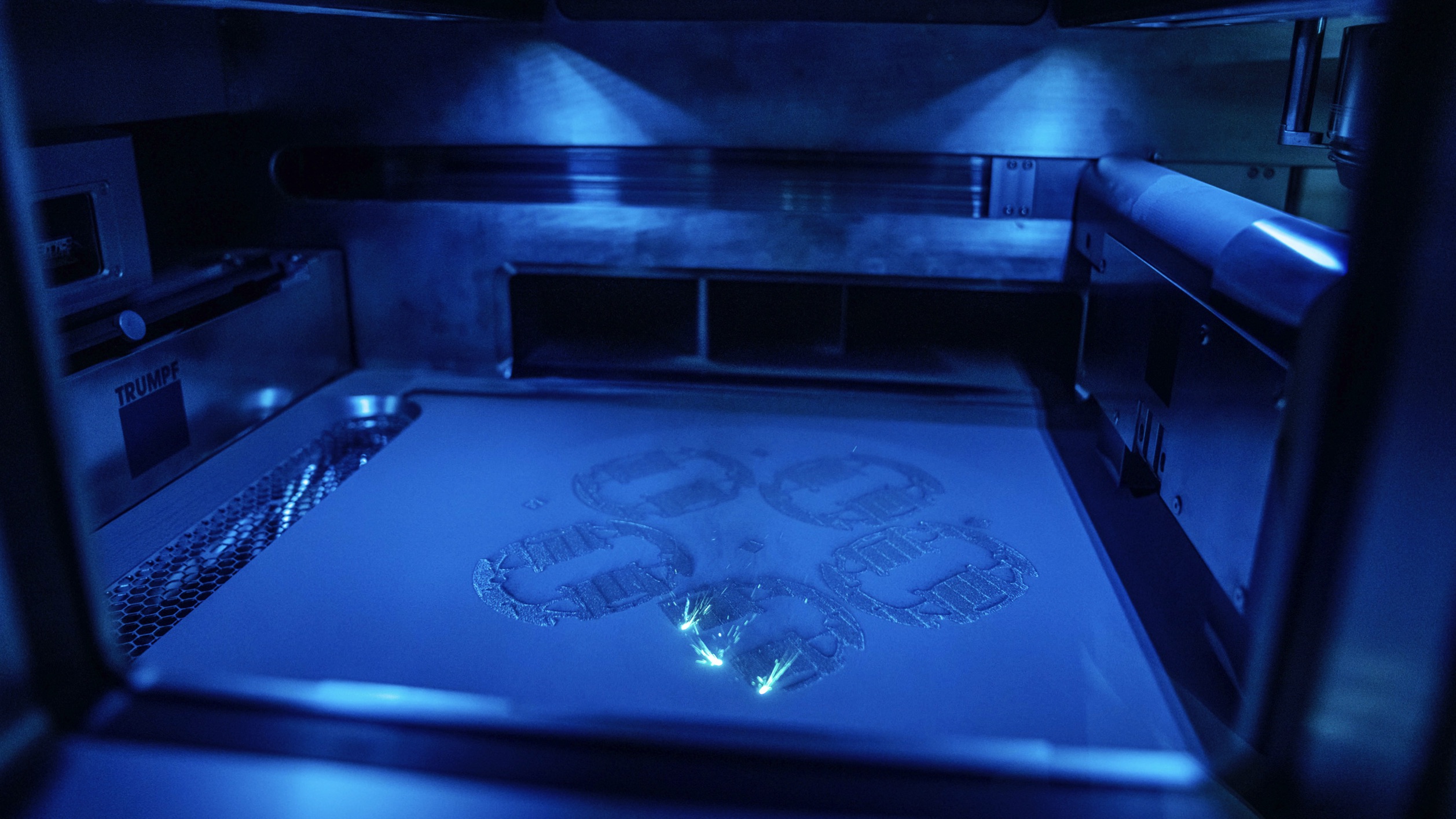

Even Samsung’s top-tier foldables come packed with ads.

Where it differs with Samsung is you are paying — for their hardware. My $1,980 Galaxy Fold is getting ads while using the phone as anyone normally would. While Samsung doesn’t tell us the profit margins on their products, it would not strain anybody’s imagination to suggest that these margins should be able to cover the cost of the services, tenfold. I could maybe understand having ads on the sub-$300 phones where margins are likely much lower, but I think we can all agree that a phone which costs anywhere near $1,000 (or in my case, far more) should not be riddled with advertisements. Margins should be high enough to cover these services, and if they don’t, Samsung is running a bad business.

These ads are showing up on my $1,980 Galaxy Fold, $1,380 Z Flip, $1,400 S20 Ultra, $1,200 S20+, $1,100 Note 10+, $1,000 S10+, and $750 S10e along with the $100 A10e. I can understand it on a $100 phone, but it is inexcusable to have them on a $750 phone, let alone a $1980 phone.

Every other major phone manufacturer provides basically the same services without requiring ads in their stock apps to subsidize them. OnePlus, OPPO, Huawei, and LG all have stock weather apps, payment apps, phone apps, and even health apps that don’t show ads. Sure, some of these OEMs include pre-installed bloatware, like Facebook, Spotify, and Netflix, but these can generally be disabled or uninstalled. Samsung’s ads can not (at least not fully).

When you consider that Samsung not only sells among the most expensive smartphones money can buy, but that it’s blatantly using them as an ad revenue platform, you’re left with one obvious conclusion: Samsung is getting greedy. Samsung is just being greedy. They hope most Samsung customers aren’t going to switch to other phones and will just ignore and deal with the ads. While that’s a very greedy and honestly just bad tactic, it was largely working until they started pushing it with more ads in more apps.

You can’t disable them

If you’re a Samsung user who’s read through all of this, you might be wondering “how do I shut off the ads?” The answer is, unfortunately, you (mostly) can’t.

You can disable Samsung Push Services, which is sometimes used to feed you notifications from Samsung apps. So disabling Push Services means no more push notification ads, but also no more push notifications at all in some Samsung apps.