The Crime Rate Perception Gap

There’s a persistent belief across America that crime is on the rise.

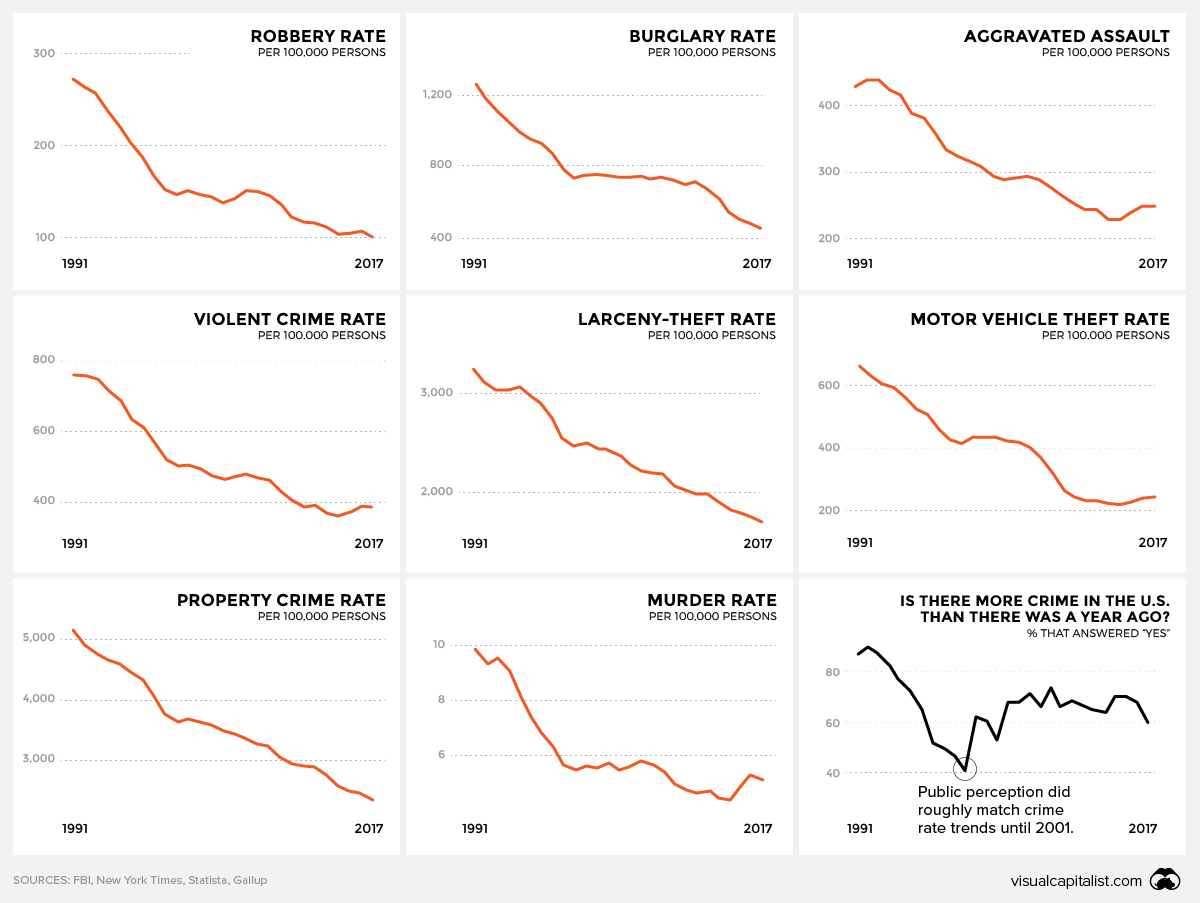

Since the late 1980s, Gallup has been polling people on their perception of crime in the United States, and consistently, the majority of respondents indicate that they see crime as becoming more prevalent. As well, a recent poll showed that more than two-thirds of Americans feel that today’s youth are less safe from crime and harm than the previous generation.

Even the highest ranking members of the government have been suggesting that the country is in the throes of a crime wave.

We have a crime problem. […] this is a dangerous permanent trend that places the health and safety of the American people at risk.

— Jeff Sessions, Former Attorney General

Is crime actually more prevalent in society? Today’s graphic, amalgamating crime rate data from the FBI, shows a very different reality.

Data vs Perception

In the early ’90s, crime in the U.S. was an undeniable concern – particularly in struggling urban centers. The country’s murder rate was nearly double what it is today, and statistics for all types of crime were through the roof.

Since that era, crime rates in the United States have undergone a remarkably steady decline, but public perception has been slow to catch up. In a 2016 survey, 57% of registered voters said crime in the U.S. had gotten worse since 2008, despite crime rates declining by double-digit percentages during that time period.

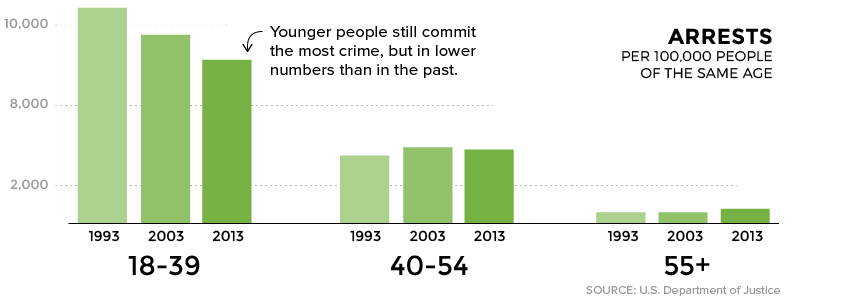

There are many theories as to why crime rates took such a dramatic U-turn, and while that matter is still a subject for debate, there’s clear data on who is and isn’t being arrested.

Are Millennials Killing Crime?

Media outlets have accused millennials of the killing off everything from department stores to commuting by car, but there’s another behavior this generation is eschewing as well – criminality.

Compared to previous generations, people under the age of 39 are simply being arrested in smaller numbers. In fact, much of the decline in overall crime can be attributed to people in this younger age bracket. In contrast, the arrest rate for older Americans actually rose slightly.

There’s no telling whether the overall trend will continue.

In fact, the most recent data shows that the murder rate has ticked up ever-so-slightly in recent years, while violent and property crimes continue to be on the decline.

A Global Perspective

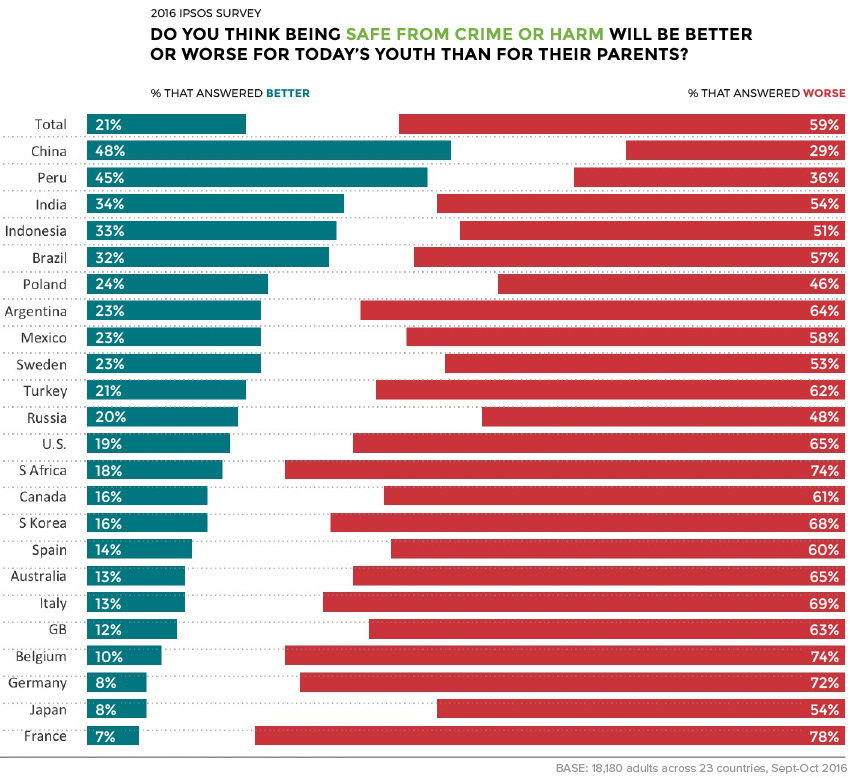

Perceptions of increasing criminality are echoed in many other developed economies as well. From Italy to South Korea, the prevailing sentiment is that youth are living in a society that is less safe than in previous generations.

As the poll above demonstrates, perception gaps exist in somewhat unexpected places.

In Sweden, where violent crime is actually increasing, 53% of people believe that crime will be worse for today’s youth. Contrast that with Australia, where crime rates have declined in a similar pattern as in the United States – yet, more than two-thirds of Aussie respondents believe that crime will be worse for today’s youth.

One significant counterpoint to this trend is China, where respondents felt that crime was less severe today than in the past.