Clouds, however, naturally reflect the sun (it’s why Venus – a planet with permanent cloud cover – shines so brightly in our night sky). Marine stratocumulus clouds are particularly important, covering around 20% of the Earth’s surface while reflecting 30% of total solar radiation. Stratocumulus clouds also cool the ocean surface directly below. Proposals to make these clouds whiter – or “marine cloud brightening” – are amongst the more serious projects now being considered by various bodies, including the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s new “solar geoengineering” committee.

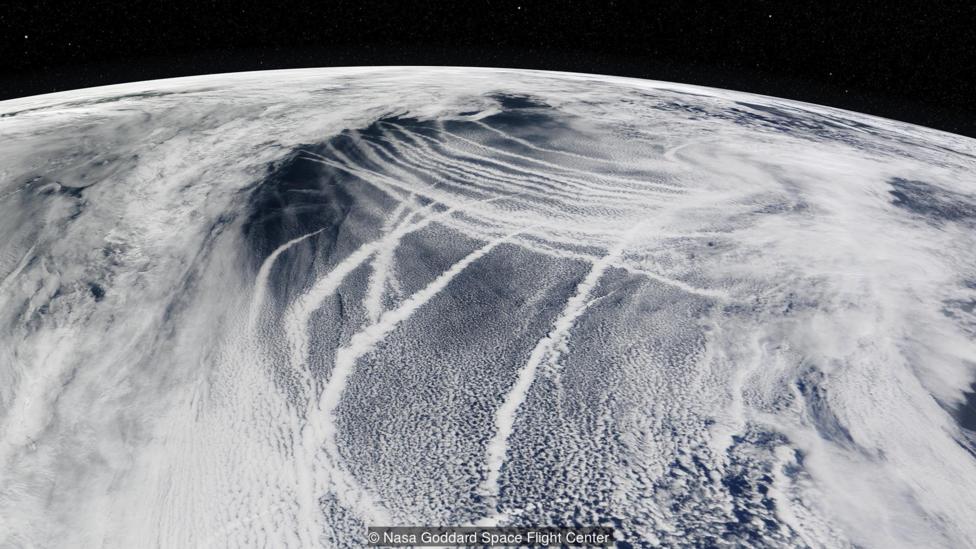

Stephen Salter, Emeritus professor at the University of Edinburgh, has been one of the leading voices of this movement. In the 1970s, when Salter was working on waves and tidal power, he came across studies examining the pollution trails left by shipping. Much like the aeroplane trails we see criss-crossing the sky, satellite imagery had revealed that shipping left similar tracks in the air above the ocean – and the research revealed that these trails were also brightening existing clouds.

The pollution particles had introduced “condensation nuclei” (otherwise scarce in the clean sea air) for water vapour to congregate around. Because the pollution particles were smaller than the natural particles, they produced smaller water droplets; and the smaller the water droplet, the whiter and more reflective it is. In 1990, British atmospheric scientist John Latham proposed doing this with benign, natural particles such as sea salt. But he needed an engineer to design a spraying system. So he contacted Stephen Salter.

The pollution trails left by ships on the ocean naturally brighten the clouds above (Credit: Nasa Goddard Space Flight Center)

Spraying about 10 cubic metres per second could undo all the [global warming] damage we’ve done to the world up till now

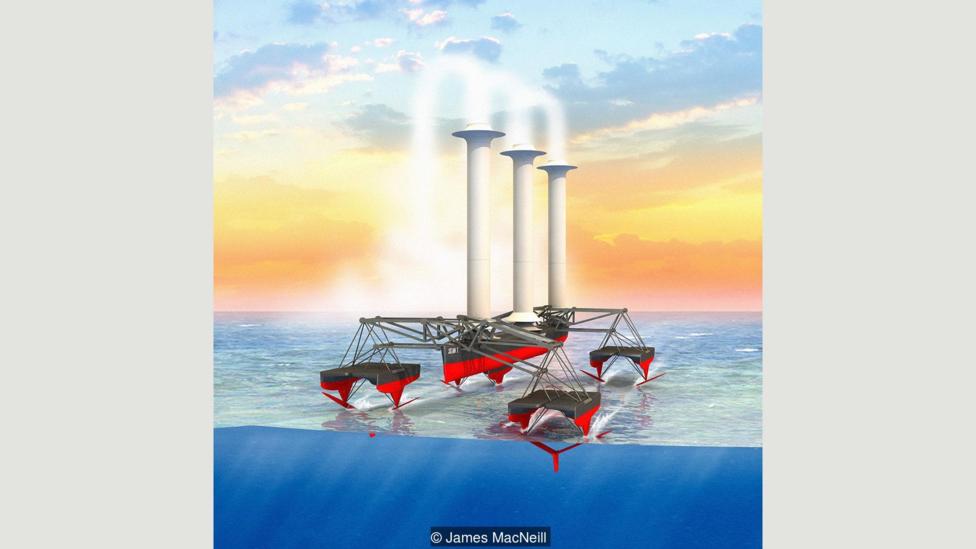

“I didn’t realise quite how hard it was going to be,” Salter now admits. Seawater, for instance, tends to clog up or corrode spray nozzles, let alone ones capable of spraying particles just 0.8 micron in size. And that’s not to mention the difficulties of modelling the effects on the weather and climate. But his latest design, he believes, is ready to build: an unmanned hydro-foil ship, computer-controlled and wind-powered, which pumps an ultra-fine mist of sea salt toward the cloud layer.

“Spraying about 10 cubic metres per second could undo all the [global warming] damage we’ve done to the world up until now,” Salter claims. And, he says, the annual cost would be less than the cost to host the annual UN Climate Conference – between $100-$200 million each year.

Salter calculates that a fleet of 300 of his autonomous ships could reduce global temperatures by 1.5C. He also believes that smaller fleets could be deployed to counter-act regional extreme weather events. Hurricane seasons and El Niño, exacerbated by high sea temperatures, could be tamed by targeted cooling via marine cloud brightening. A PhD thesis from the University of Leeds in 2012 stated that cloud brightening could, “decrease sea surface temperatures during peak tropical cyclone season… [reducing] the energy available for convection and may reduce intensity of storms”.

Salter boasts that 160 of his ships could “moderate an El Niño event, and a few hundred [would] stop hurricanes”. The same could be done, he says, to protect large coral reefs such as the Great Barrier Reef, and even cool the polar regions to allow sea ice to return.

Hazard warning

So, what’s the catch? Well, there’s a very big catch indeed. The potential side-effects of solar geoengineering on the scale needed to slow hurricanes or cool global temperatures are not well understood. According to various theories, it could prompt droughts, flooding, and catastrophic crop failures; some even fear that the technology could be weaponised (during the Vietnam War, American forces flew thousands of “cloud seeding” missions to flood enemy troop supply lines). Another major concern is that geoengineering could be used as an excuse to slow down emissions reduction, meaning CO2 levels continue to rise and oceans continue to acidify – which, of course, brings its own serious problems.

Stephen Salter believes that a fleet of 300 of his autonomous ships could reduce global temperatures by 1.5C (Credit: James MacNeill)

A rival US academic team – The MCB Project – is less gung-ho than Salter. Kelly Wanser, the principal director of The MCB Project, is based in Silicon Valley. When it launched in 2010 with seed funding from the Gates Foundation, it received a fierce backlash. Media articles talked of “cloud-wrenching cronies” and warned of the potential for “unilateral action on geoengineering”. Since then, Wanser has kept relatively low-key.

Her team’s design is similar to commercial snow-making machines for ski resorts, yet capable of spraying “particles ten thousand times smaller [than snow]… at three trillion particles per second”. The MCB Project hopes to test this near Monterey Bay, California, where marine stratocumulus clouds waft overland. They would start with a single cloud to track its impact.

“One of the strengths of marine cloud brightening is it can be very gradually scaled,” says Wanser. “You [can] get a pretty good grasp of whether and how you are brightening clouds, without doing things that impact climate or weather.”

Such a step-by-step research effort, says Wanser, would take a decade at least. But due to the controversy it attracts, this hasn’t even started yet. Not one cloud has yet been purposefully brightened by academics – although cargo shipping still does this unintentionally, with dirty particles, every single day.

Source: BBC – Future – How artificially brightened clouds could stop climate change

Robin Edgar

Organisational Structures | Technology and Science | Military, IT and Lifestyle consultancy | Social, Broadcast & Cross Media | Flying aircraft