The World-Check database used by businesses to verify the trustworthiness of users has fallen into the hands of cybercriminals.

The Register was contacted by a member of the GhostR group on Thursday, claiming responsibility for the theft. The authenticity of the claims was later verified by a spokesperson for the London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG), which maintains the database.

A spokesperson said the breach was genuine, but occurred at an unnamed third party, and work is underway to further protect data.

“This was not a security breach of LSEG/our systems,” said an LSEG spokesperson. “The incident involves a third party’s data set, which includes a copy of the World-Check data file.

“This was illegally obtained from the third party’s system. We are liaising with the affected third party, to ensure our data is protected and ensuring that any appropriate authorities are notified.”

The World-Check database aggregates information on undesirables such as terrorists, money launderers, dodgy politicians, and the like. It’s used by companies during Know Your Customer (KYC) checks, especially by banks and other financial institutions to verify their clients are who they claim to be.

No bank wants to be associated with a known money launderer, after all.

World-Check is a subscription-only service that pulls together data from open sources such as official sanctions lists, regulatory enforcement lists, government sources, and trusted media publications.

We asked GhostR about its motivations over email, but it didn’t respond to questioning. In the original message, the group said it would begin leaking the database soon. The first leak, so it claimed, will include details on thousands of individuals, including “royal family members.”

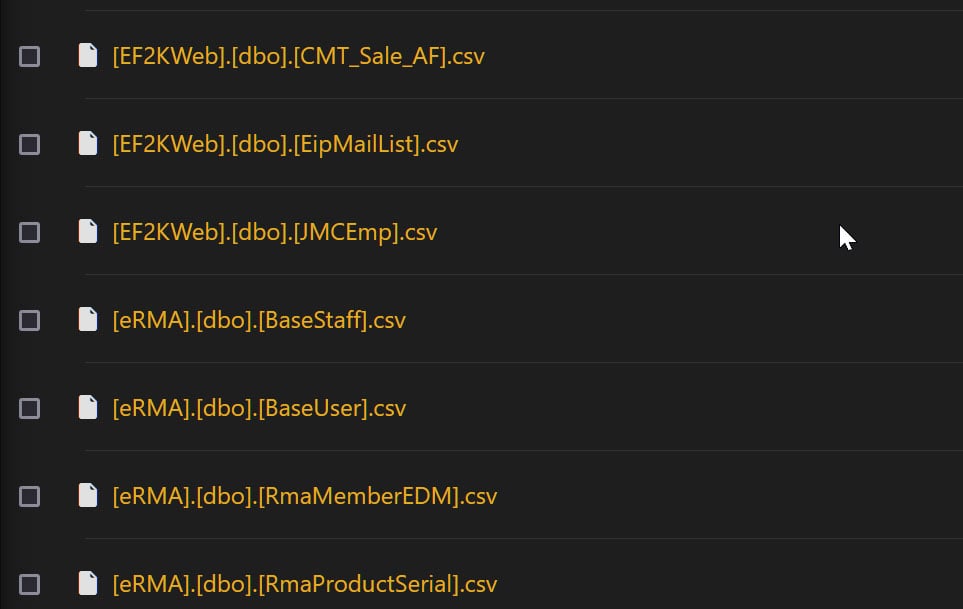

The miscreants provided us with a 10,000-record sample of the stolen data for our perusal, and to verify their claims were genuine. The database allegedly contains more than five million records in total.

A quick scan of the sample revealed a slew of names from various countries, all on the list for different reasons. Political figures, judges, diplomats, suspected terrorists, money launderers, drug lords, websites, businesses – the list goes on.

Known cybercriminals also appear on the list, including those suspected of working for China’s APT31, such as Zhao Guangzong and Ni Gaobin, who were added to sanctions lists just weeks ago. A Cypriot spyware firm is also nestled in the small sample we received.

World-Check data includes full names, the category of person (such as being a member of organized crime or a political figure), in some cases their specific job role, dates and places of birth (where known), other known aliases, social security numbers, their gender, and a small explanation of why they appear on the list.

Long term readers will remember that a previous edition of the database was leaked in 2016 back when World-Check was owned by Thomson Reuters. Back then, only 2.2 million records were included, so the current version implicates many more individuals, entities, and vessels.

A month later, the database was reportedly being flogged online, with copies fetching $6,750 a pop.

Despite aggregating data from what are supposed to be reliable sources, being added to the World-Check list has been known in the past to affect innocent people. At the time of the first leak nearly eight years ago, investigations revealed inaccuracies in its data and a range of false terrorism designations.

Various Britons were found to have had their HSBC bank accounts closed in 2014 after they were allegedly added to the World-Check list in error.

[…]

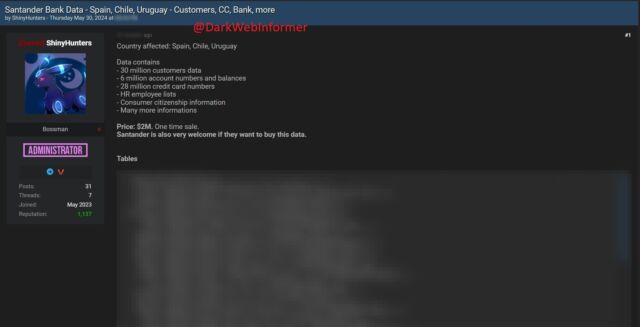

Cloud storage provider Snowflake said that accounts belonging to multiple customers have been hacked after threat actors obtained credentials through info-stealing malware or by purchasing them on online crime forums.

Cloud storage provider Snowflake said that accounts belonging to multiple customers have been hacked after threat actors obtained credentials through info-stealing malware or by purchasing them on online crime forums.