Swarm Technologies Inc will pay a $900,000 fine for launching and operating four small experimental communications satellites that risked “satellite collisions” and threatened “critical commercial and government satellite operations,” the Federal Communications Commission said on Thursday.

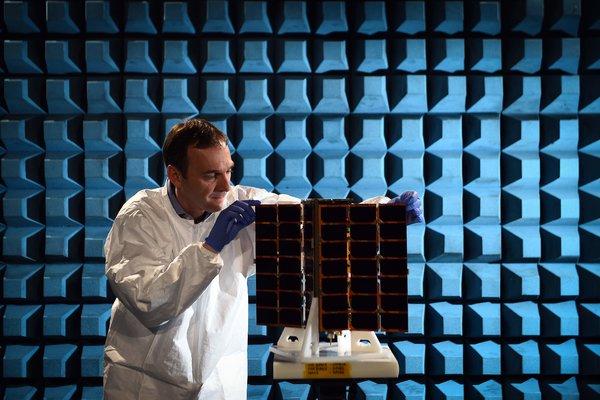

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) logo is seen before the FCC Net Neutrality hearing in Washington February 26, 2015. REUTERS/Yuri GripasThe California-based start-up founded by former Google and Apple engineers in 2016 also agreed to enhanced FCC oversight and a requirement of pre-launch notices to the FCC for three years.

Swarm launched the satellites in India last January after the FCC rejected its application to deploy and operate them, citing concerns about the company’s tracking ability.

It said Swarm had unlawfully transmitted signals between earth stations in the state of Georgia and the satellites for over a week. The investigation also found that Swarm performed unauthorized weather balloon-to-ground station tests and other unauthorized equipment tests prior to the satellites’ launch.

Swarm aims to provide low-cost space-based internet service and plans eventually to use a constellation of 100 satellites.

Swarm won permission in August from the FCC to reactivate the satellites and said then it is “fully committed to complying with all regulations and has been working closely with the FCC,” noting that its satellites are “100 percent trackable.”

Source: FCC fines Swarm $900,000 for unauthorized satellite launch | Reuters